A programming language

Using cargo:

cargo install quilt-lang

Using docker:

docker run --rm -t ghcr.io/quilt-lang/quilt

quilt examples/hello_world.png

quilt --pixel-size 20 examples/hello_world_x20.png

- Run all checks:

make check - Scale images using ImageMagick:

convert -scale 500% foo.png foo_x5.png - Build docker image:

docker build . -t quilt:<TAG>

Unlike other programming languages, quilt takes a maximalist approach to building programs. Instead of 'as simple as possible and no simpler', quilt programmers are encouraged to build elaborate, colorful, and ornate programs.

Programs in quilt are constructed by crafting images that are made of pixels. By default, each pixel will be considered to have a width and height of 1, but this can be adjusted with the --pixel-size command-line argument.

Each instruction is defined as a range of hue values, to give the programmer some flexibility over the color of their programs. Hue is the only parameter considered; saturation and lightness are ignored.

Execution begins at the START pixel, which has a hue of exactly 300; this is the only instruction that is not a range of hues.

Execution continues along roads. Roads are perhaps the most common quilt instruction and tell the program where to 'go'. This means that quilt programs, in addition to having a program counter, also have a direction.

There are rules about where execution will go to next when faced with multiple instructions to execute/roads to follow:

- Roads are always given top priority over any other instruction

- If there is more than one road to take, precendence is applied in the following order:

- The road 'ahead' (in the same direction as the current direction) is taken first, if it exists. If not, quilt next considers the clockwise direction, and then the counter-clockwise direction. If there are no roads in any of these three directions, quilt will take the instruction 'ahead'. If there is no instruction ahead (this means the program counter is at the bounds of an image), execution will turn around and return the way it came, no matter if there is a road in that direction or not. This means previously executed instructions will be repeated in reverse order.

This precedence is similar to driving in right-hand driving systems. Instructions on the 'right' (counter-clockwise direction) are always considered before others; the only exception is that the forward direction is attempted first; then right, then left, then back.

Some quilt instructions take arguments. The argument will always be the pixel following the instruction in whatever direction execution is oriented. The value of the argument will be the hue of that pixel. This means all arguments have a maximum value of 360, since that is the maximum value for hue. When a pixel is consumed as an argument, it is treated as data. The same pixel, if execution encounters it from a different direction, can also be treated as an instruction.

Quilt provides a stack, an address register, and a tape (a one-dimensional array). To access the tape, you must push an address into the address register with the MOVA command (the 'A' stands for 'address'), followed by the address. To store data in the tape, use the SAVE command, which writes to tape[<address in address register>]. You can push constants to the stack with PUSH, followed by a data pixel with a hue value that you want to push. POP pops from the stack and discards the result. POPA pops from the stack and writes it to tape[<address in address register>]. PUSHA copies the value from tape[<address in address register>] and pushes it to the stack. All arithmetic instructions like ADD, SUB, etc, pop the two arguments from the stack and push the result.

There are two instructions that deserve special attention: pop-until and output-until. These commands both pop from stack until a certain condition is reached, and output-until also outputs the values it pops from the stack. By default, they compare each popped element from the stack to 0 and only stop once the popped element is equal to 0. This logic can be changed with conditionals.

Conditionals are sort of like loop arguments that tell the instruction which kind of comparison to perform. There are six: equal, not equal, less than, less than or equal to, greater than, and greater than or equal to. Placing a conditional at the corner of a loop will signal to the loop which comparison to use. The conditional ranges are listed below:

| hue range | comparison |

|---|---|

| default | Equal |

| 0-8 | NotEqual |

| 72-80 | Less |

| 144-152 | LessEqual |

| 216-224 | Greater |

| 288-296 | GreaterEqual |

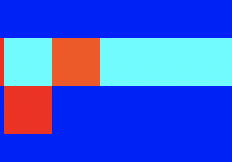

A corner is defined as one pixel backwards and one pixel clockwise:

In the example above (taken from fib(n) -- see below), the direction at this point of the program is East. The orange pixel in the road has a hue of 18 and so is a pop-until. It's conditional is the red pixel one square back and one square in the clockwise direction (if you are travelling east, this would be to the right of the square before the pop-until). It has a hue of 0, and so tells the pop-until instruction to pop elements from the loop until it finds one that is not equal to 0 (see the chart above). If a conditional in the above ranges is not provided, all pop-until and output-until instructions will continue until finding a 0.

Popping from the stack is the only way to halt the program: a graceful exit is to pop from the stack when there are no elements remaining.

The following is a table taken from commands.md:

| command name | hue range |

|---|---|

PUSHA |

0-8 |

POP UNTIL |

18-26 |

PUSH <number> |

36-44 |

SAVE <number> |

54-62 |

MOVA <address> |

72-80 |

POPA |

90-98 |

ADD |

108-116 |

SUB |

126-134 |

MULT |

144-152 |

DIV |

162-170 |

ROAD |

180-188 |

LEFTSHIFT |

198-206 |

RIGHTSHIFT |

216-224 |

AND |

234-242 |

OR |

252-260 |

NOT |

270-278 |

XOR |

288-296 |

OUTPUT |

306-314 |

OUTPUT UNTIL |

324-332 |

MODULO |

342-350 |

START |

300 |

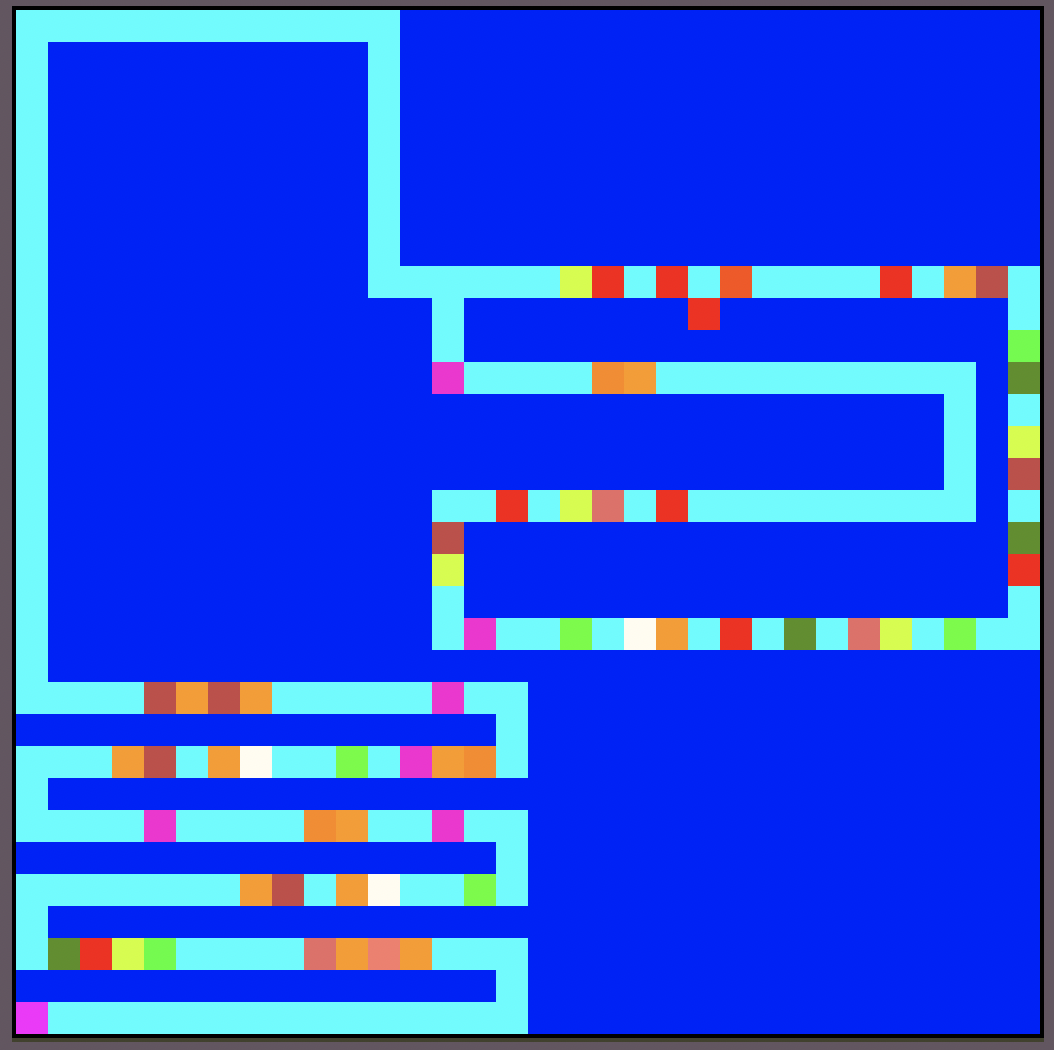

This quilt program prints Hello world! to stdout, followed by a newline. All output in quilt is text to stdout. There is no standard library, so no other output formats are supported.

Execution starts at the bottom left corner of the image. This pixel has a hue of 300, so it is the start pixel. Quilt then follows the cyan road in a spiral to the center of the image, where there are other instructions. The first thing that happens after following the road is to reach the initial orange pixel, which has a hue of 36. Consulting the above table, we see that this is a push instruction. Since the road has turned south, execution is oriented south and that is where it expects the argument. The red pixel following the push has a hue of 0, and is the argument. So now the stack has a 0 pushed to it. Then we push a 10: \n. You can see that we do a series of pushes, sometimes with roads in between to turn execution and continue the spiral pattern. We are pushing the ascii representation of the rest of Hello world in reverse. After quilt reads the top-right yellow pixel of the inner loop, the stack looks like this: 0 10 33 100 108 114 111 119 32 111 108 108 101 72 (this is ascii of Hello world!\n\0 backwards). Then we follow the road until we end at the pink square with a hue of 324. Looking above, we see this is the output-until instruction, which pops from the stack and outputs until it sees a 0.

All the purple in the image in between the cyan roads is technically an or instruction, but is never executed due to the precendence rules of quilt, so can technically be any color, except a road.

Since there is no input, to calculate fib(n), n must be hardcoded into the program. Changing the hue of the pixel at (11, 29) will change n. In this image, it is 6. Also, quilt provides no way to print digits with a length of more than one, so for inputs > 6 (where fib(n).to_string().len() > 1) the output will only be viewable as ascii characters with the corresponding value of fib(n).

This program prints 1 1 2 3 5 8 to stdout. How it works is left as an exercise for the reader.