generated from cotes2020/chirpy-starter

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 0

Commit

This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository.

- Loading branch information

1 parent

648fbd6

commit 137693a

Showing

2 changed files

with

257 additions

and

0 deletions.

There are no files selected for viewing

190 changes: 190 additions & 0 deletions

190

...oduction to Machine Learining/2024-12-3-IML-7.2-Principal component analysis.md

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -0,0 +1,190 @@ | ||

| --- | ||

| layout: post | ||

| title: IML L7.2 Principal component analysis | ||

| author: wichai | ||

| date: 2024-12-3 14:00 +0000 | ||

| categories: [Study, Master] | ||

| tags: [DU, AI, ML] | ||

| mermaid: true | ||

| math: true | ||

| pin: false | ||

| --- | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # Principal component analysis | ||

|

|

||

| If we have many features, odds are that many are correlated. If there are strong relationships between features, we might not need all of them. | ||

|

|

||

| With *principal component analysis* we want to extract the most relevant/independant combination of features. | ||

|

|

||

| It is important to realise that PCA only looks at the features without looking at the labels, it is an example of *unsupervised learning*. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Correlated vs uncorrelated | ||

|

|

||

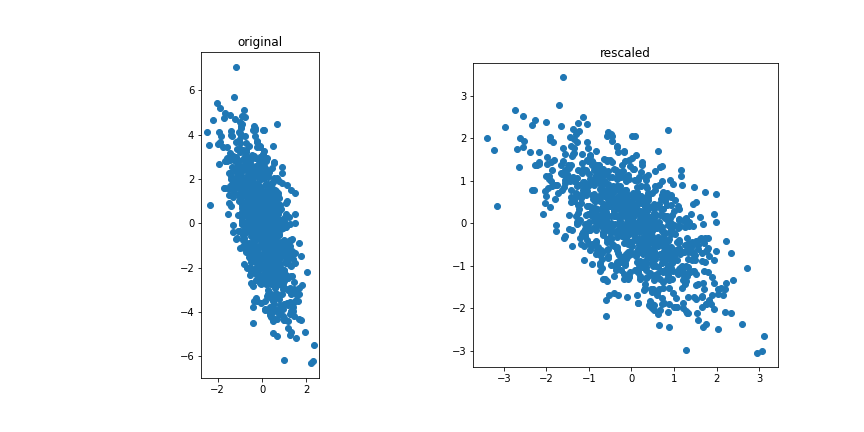

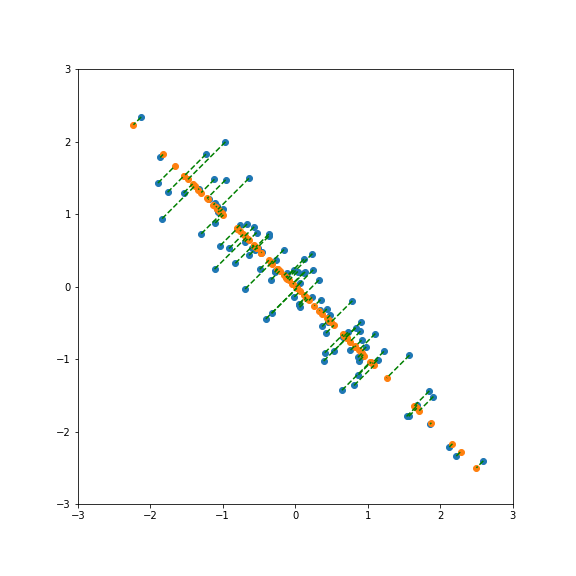

| Correlated features | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

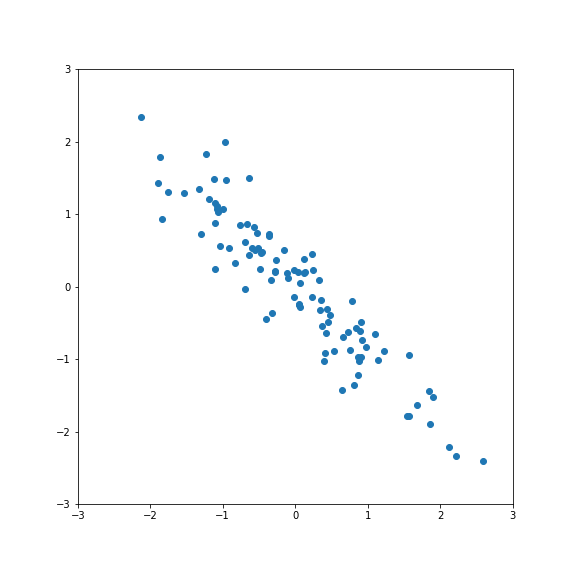

| Uncorrelated features: | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

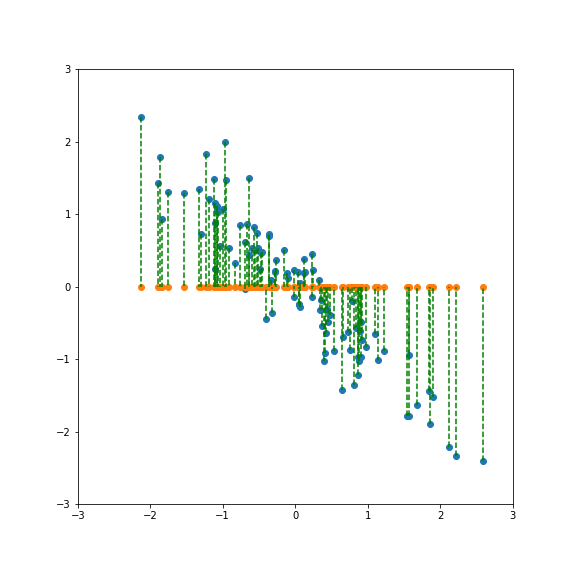

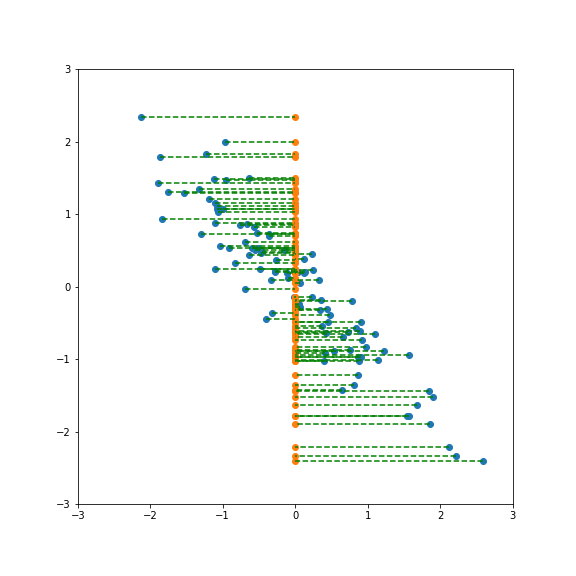

| The idea for PCA is to project the data on a subspace with fewer dimensions.  | ||

|

|

||

| The data is standardised. | ||

|

|

||

| If we project onto the first component we get variance 1:  | ||

|

|

||

| If we project onto the second component we also get variance 1:  | ||

|

|

||

| But projecting onto a different direction gives a different variance, here larger than 1:  | ||

|

|

||

| And here smaller than one:  | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Performing PCA gives a new basis in feature space that include the direction of largest and smallest variance. | ||

|

|

||

| There is no guarantee that the most relevant features for a given classification tasks are going to have the largest variance. | ||

|

|

||

| If there is a strong linear relationship between features it will correspond to a component with a small variance, so dropping it will not lead to a large loss of variance but will reduce the dimensionality of the model. | ||

|

|

||

| ## Finding the principal components | ||

|

|

||

| The first step is to normalise and center the features. | ||

|

|

||

| xi→axi+bxi→axi+b | ||

|

|

||

| such that | ||

|

|

||

| ⟨xi⟩=0,⟨x2i⟩=1⟨xi⟩=0,⟨xi2⟩=1 | ||

|

|

||

| The covariance matrix of the data is then given by | ||

|

|

||

| σ=XTXσ=XTX | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| If XX is the nd×nfnd×nf data matrix of the ndnd training samples with nfnf features. The covariance matrix is a nf×nfnf×nf matrix. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| If we diagonalize σσ | ||

|

|

||

| σ=SDS−1σ=SDS−1 | ||

|

|

||

| where the columns of SS are the eigenvectors of σσ. | ||

|

|

||

| the eigenvectors with the highest eigenvalues correspond to the axis with the highest variance. PCA reduces the dimensionality of the data by projecting unto the subspace spanned by the eignevectors with the kk highest eigenvalues. | ||

|

|

||

| Xk=XSkXk=XSk | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| where SkSk is the nf×knf×k matrix composed of the kk highest eigenvectors. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Singular value decomposition | ||

|

|

||

| There is a shortcut to computing the full data variance to calculate the principal component analysis. Using *singular value decomposition*, we can write XX as | ||

|

|

||

| X=UΣVX=UΣV | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| where UU is an orthogonal nd×ndnd×nd matrix, ΣΣ is a nd×nfnd×nf matrix with non-vanishing elements only on the diagonal and VV is a nf×nfnf×nf orthogonal matrix. | ||

|

|

||

| using this decomposition we have | ||

|

|

||

| XTX=VTΣTUTUΣV=V−1ΣTΣVXTX=VTΣTUTUΣV=V−1ΣTΣV | ||

|

|

||

| The combination ΣTΣΣTΣ is diagonal so we see that the matrix V is the change of basis needed to diagonalise XTXXTX. So we only need to perform the SVD of X to find the eigenvectors of XTXXTX. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Data sample variance | ||

|

|

||

| The total variance of a data (zero-centered) sample is given by | ||

|

|

||

| σtot=⟨∑iX2i⟩=1N−1∑sample∑ix2i=1N−1Tr(XTX).σtot=⟨∑iXi2⟩=1N−1∑sample∑ixi2=1N−1Tr(XTX). | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The trace is invariant under rotations in the feature space so it is equal to the trace of the diagonalised matrix Tr(σ)=∑EjTr(σ)=∑Ej where EjEj are the eigenvalues of XTXXTX. | ||

|

|

||

| If we have the SVD decomposition of XX we can express these eigenvalues in term of the diagonal elements ϵjϵj of ΣΣ: | ||

|

|

||

| Tr(σ)=∑Ej=∑jϵ2j | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Explained variance | ||

|

|

||

| When we only consider the kk principal axis of a dataset we will loose some of the variance of the dataset. | ||

|

|

||

| Assuming the eigenvalues are ordered in size we have | ||

|

|

||

| σk≡Tr(XTkXk)=k∑j=1ϵ2jσk≡Tr(XkTXk)=∑j=1kϵj2 | ||

|

|

||

| σkσk is the variance our reduced dataset retained from the original, it is often referred as the *explained variance*. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Example: 8x8 digits pictures | ||

|

|

||

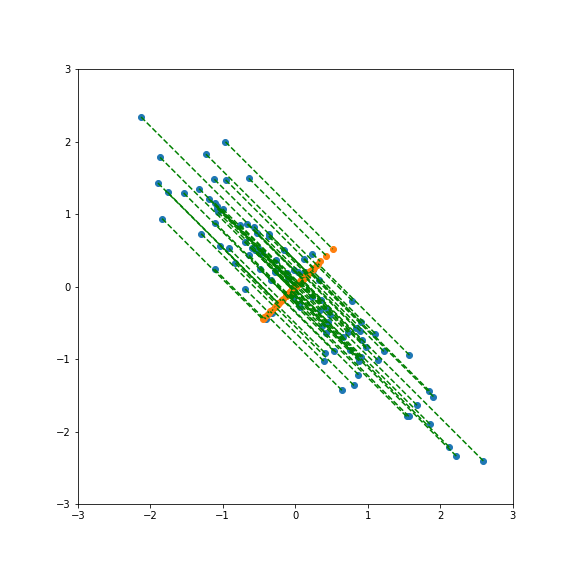

| We consider a dataset of handwritten digits, compressed to an 8x8 image: | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| These have a 64-dimensional space but this is clearly far larger than the true dimension of the space: | ||

|

|

||

| - only a very limited subset of 8x8 pictures represent digits | ||

| - the corners are largely irrelevant hardly ever used | ||

| - digits are lines, so there is a large correlation between neighbouring pixels. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| PCA should help us limit our features to things that are likely to be relevant. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

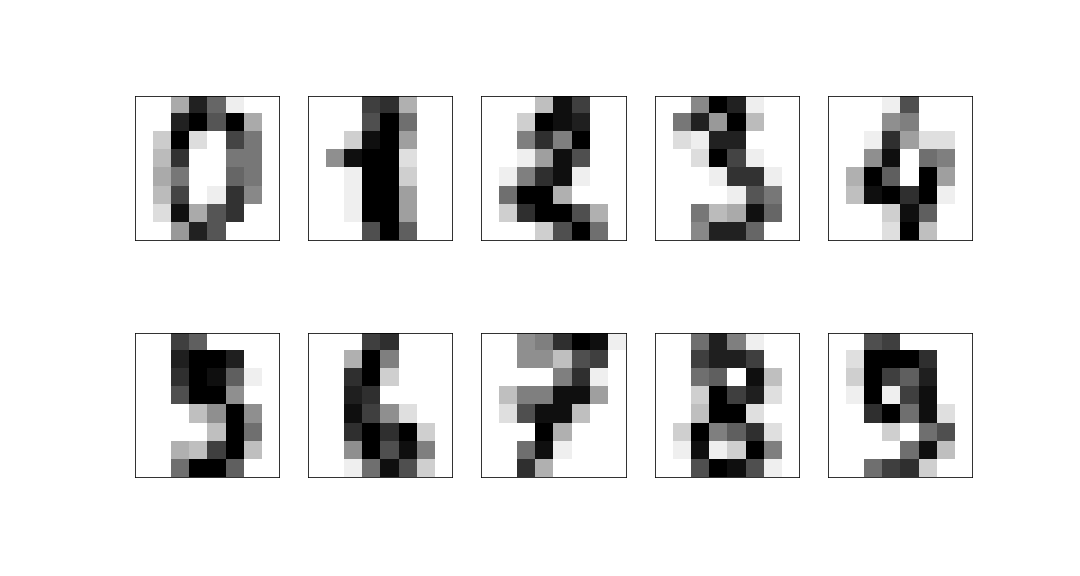

| Performing PCA we can see how many eigenvectors are needed to reproduce a given fraction of the dataset variance: | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| We can keep 50% of the dataset variance with less than 10 features. | ||

|

|

||

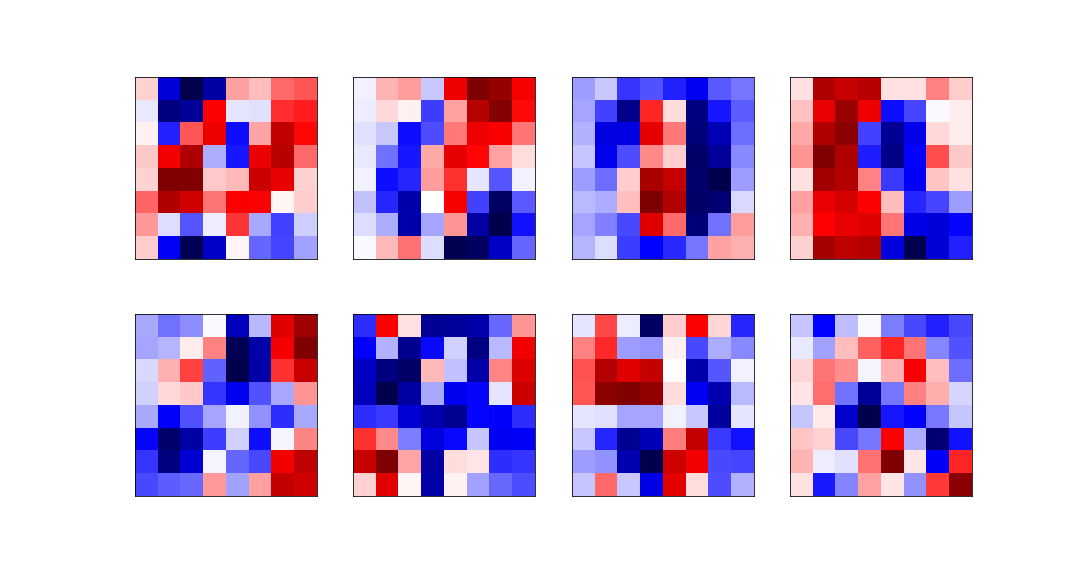

| he eight most relevant eigenvectors are: | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

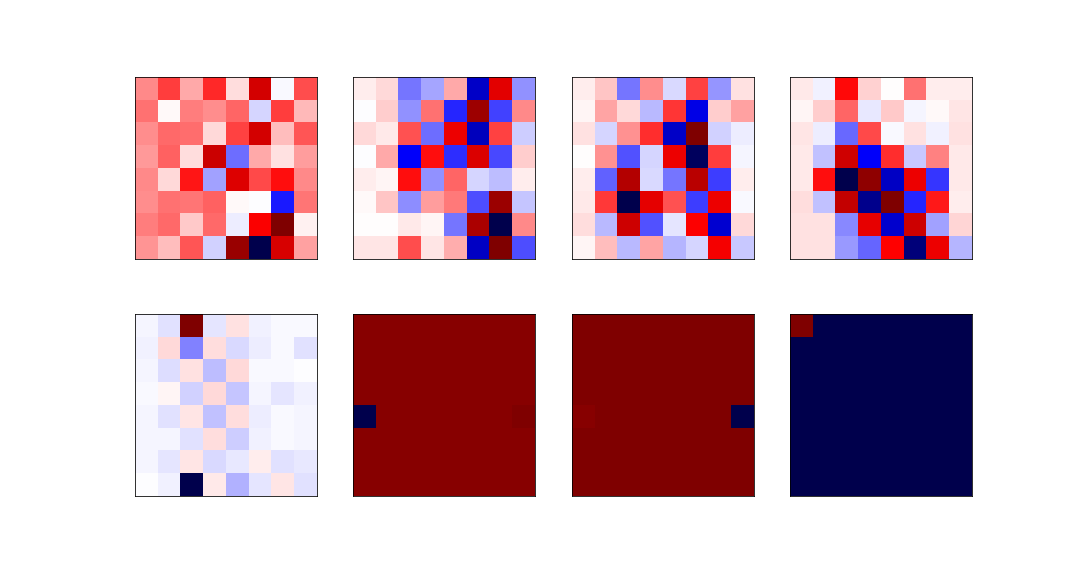

| The least relevant eigenvectors are: | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

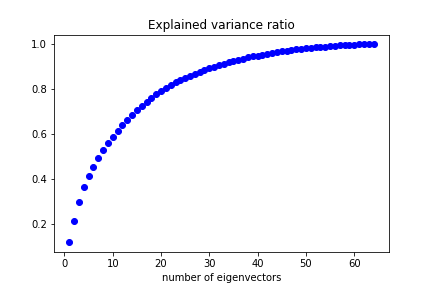

| ## Data visualisation | ||

|

|

||

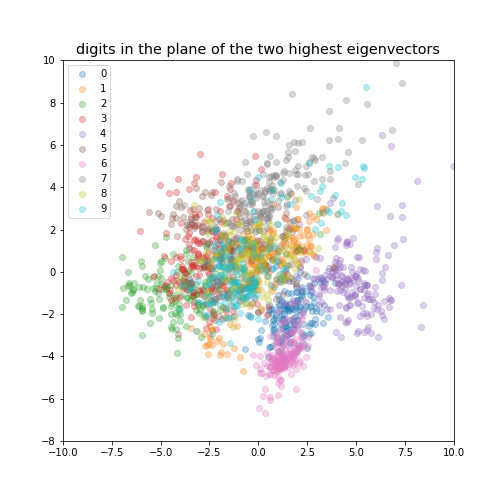

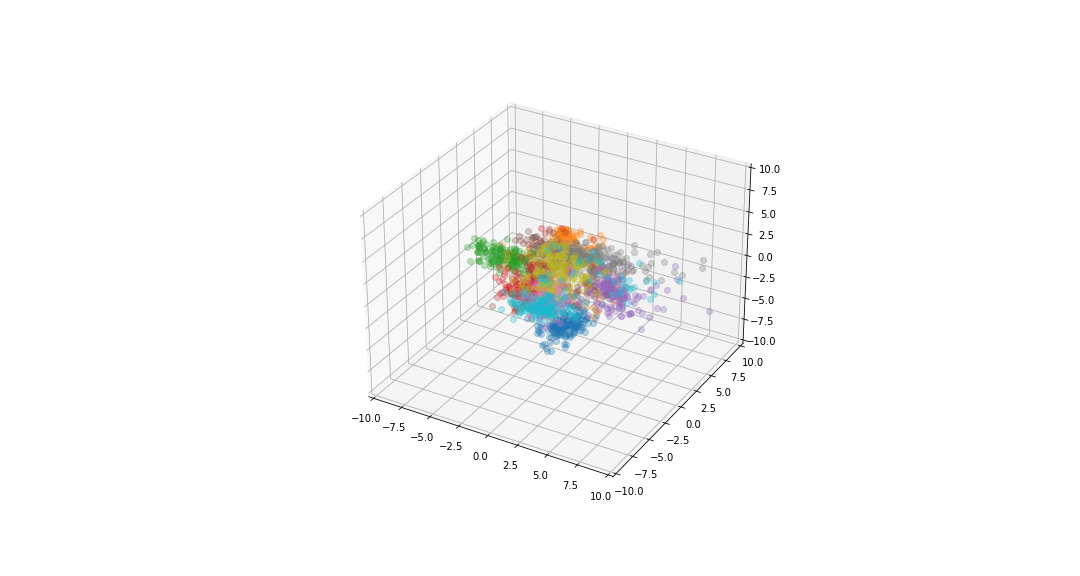

| If we reduce the data to be 2-dimensional or 3-dimensional we can get a visualisation of the data. | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| ### digits in the plane of the two highest eigenvectors | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

67 changes: 67 additions & 0 deletions

67

...oduction to Machine Learining/2024-12-3-IML-L7.1-The curse of dimensionality.md

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -0,0 +1,67 @@ | ||

| --- | ||

| layout: post | ||

| title: IML L7.1 The curse of dimensionality | ||

| author: wichai | ||

| date: 2024-12-3 14:00 +0000 | ||

| categories: [Study, Master] | ||

| tags: [DU, AI, ML] | ||

| mermaid: true | ||

| math: true | ||

| pin: false | ||

| --- | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| # The curse of dimensionality | ||

|

|

||

| One would think that the more features one has to describe samples in a dataset the better one would be able to perform a classification task. Unfortunately with the increase of the number of features comes the difficulty of fitting a multi-dimensional model. | ||

|

|

||

| This is generally referred to as the *curse of dimensionality* and we will see a few surprising effects that explain why more features can make life difficult. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## How many points are in the center of the cube? | ||

|

|

||

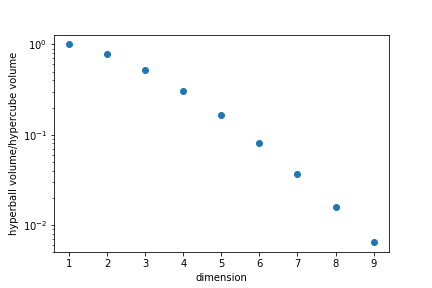

| We can ask the question "In the hypercube −1≤xi≤1−1≤xi≤1, how many points are no further apart to the center than 1?" | ||

|

|

||

| This is equivalent to asking what is the ratio of the unit "ball" to the volume of the smallest "cube" enclosing it. | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| In high dimensions most points are in "corners" rather than in the "centre". | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Average distance between two random points | ||

|

|

||

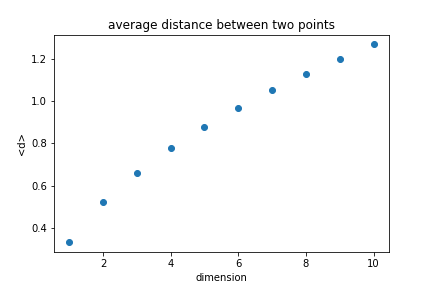

| Looking at the unit cube, we can calculate the average distance between any two points. | ||

|

|

||

| d=√∑ix2id=∑ixi2 | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| The average distance increases with the dimension. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

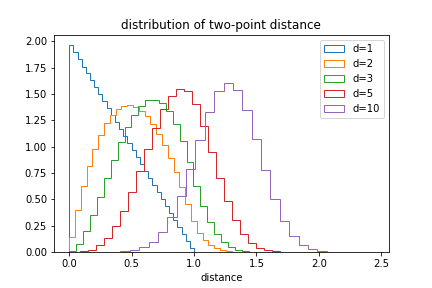

| We can also plot the distribution of distances: | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| The likelihood of small distances drops as the dimension increases. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| ## Proximity to edges | ||

|

|

||

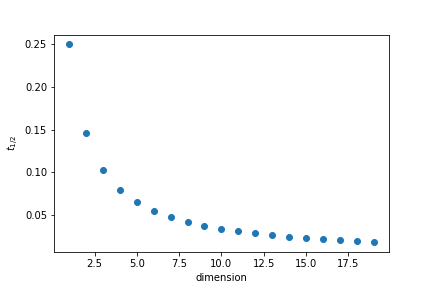

| One interesting question to ask is how close to the edges points are. To quantify it we will calculate what is the thickness tt of the outer layer of the unit cube that contain half the points if the points are randomly distributed. | ||

|

|

||

| The volume inside is given by | ||

| $$ | ||

| $$ | ||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| In 35 dimensions half of the points are in a outer layer 0.01 thin. |