From 3dfb54db26ca99bd27bb92946a6621d9135fd84b Mon Sep 17 00:00:00 2001

From: Omoaholo <157885733+Omoaholo@users.noreply.github.com>

Date: Sat, 10 Feb 2024 00:13:08 +0100

Subject: [PATCH] Update 02-00-introduction.md

- A paragraph on the African perspective.

- A section on "Geopolitics and the Evolution of Technology and Democracy"

- Attempted to resolve edit conflicts.

---

contents/english/02-00-introduction.md | 46 ++++++++++++++------------

1 file changed, 24 insertions(+), 22 deletions(-)

diff --git a/contents/english/02-00-introduction.md b/contents/english/02-00-introduction.md

index 13742fa2..595c2e45 100644

--- a/contents/english/02-00-introduction.md

+++ b/contents/english/02-00-introduction.md

@@ -10,14 +10,14 @@ Anxiety over technology and geopolitics is pervasive today. Yet there is a more

The dominant trends in technology in recent decades have been artificial intelligence and blockchains. These have, respectively, empowered centralized top-down control and turbo-charged atomized polarization and financial capitalism. Both outcomes are corrosive to the values of democratic pluralism. It is little surprise, then, that technology is widely seen as one of the greatest threats to democracy and as a powerful tool for both external authoritarians and those who would subvert democracies from within.

-At the same time, democracy was once a radical experiment to scale the governance of a city-state to many millions of citizens spread across continents. Today it has become a synonym in much of the world for the increasingly desperate effort to preserve rigid, outmoded, polarized, paralyzed, and increasingly illegitimate governments. We should not be shocked, therefore, at the disdain of so many technologists have for democratic participation as an impediment to progress, and by the fear that so many of advocates of democracy that technical advance will bring the dominance of authoritarian adversaries or internal collapse.

+At the same time, democracy was once a radical experiment to scale the governance of a city-state to many millions of citizens spread across continents. Today it has become a synonym in much of the world for the increasingly desperate effort to preserve rigid, outmoded, polarized, paralyzed, and increasingly illegitimate governments. We should not be shocked, therefore, at the disdain that so many technologists have for democratic participation, viewing it as an impediment to progress, nor should we be surprised by the fear among so many advocates of democracy that technical advance will result in the dominance of authoritarian adversaries or internal collapse.

-In this book we hope to show that this tragic conflict is avoidable, that properly conceived technology and democracy can be powerful and natural allies. However, it is no accident that arguments in this direction evoke eye-rolling in many quarters. A gulf of grievance and distrust between the two sides of this divide has developed over the last decade and will not easily be laid to rest. Only by fully acknowledging and embracing the legitimate concerns and critiques of both sides of this conflict shall we have a chance of seeing its root cause and seeking to transcend it. Thus, we begin by drawing out these grievances with a generous spirit, accepting critiques that have raised broad concerns even when they are imperfectly supported by the available evidence. Trying to reconcile these extreme divergences offers an opportunity to raise the ambition of democratic technology.

+In this book, we hope to show that this tragic conflict is avoidable and that, properly conceived, technology and democracy can be powerful and natural allies. However, it is no accident that arguments in this direction evoke eye-rolling in many quarters. A gulf of grievance and distrust between the two sides of this divide has developed over the last decade and will not easily be laid to rest. Only by fully acknowledging and embracing the legitimate concerns and critiques of both sides of this conflict shall we have a chance to see its root cause and seek to transcend it. Thus, we begin by drawing out these grievances with a generous spirit, accepting critiques that have raised broad concerns even when they are imperfectly supported by the available evidence. Trying to reconcile these extreme divergences offers an opportunity to raise the ambition of democratic technology.

### Technology’s Attack on Democracy

-The last decade of information technology threatens democracy in two related and yet at the same time opposite ways. As Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson famously argued, free democratic societies exist in a “narrow corridor” between social collapse and authoritarianism[^NarrowCorridor]. From both sides, information technologies seem to be narrowing the corridor, squeezing the possibility of a free society.

+The last decade of information technology has threatened democracy in two related yet opposite ways. As Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson famously argued, free democratic societies exist in a “narrow corridor” between social collapse and authoritarianism[^NarrowCorridor]. From both sides, information technologies seem to be narrowing the corridor, squeezing the possibility of a free society.

On the one hand, technologies (e.g., social media, cryptography and some other financial technology) are breaking down the social fabric, heightening polarization, eroding norms, undermining law enforcement and accelerating the speed and expanding the reach of financial markets to the point where they are unaccountable to democratic polities. We shall call these threats “anti-social”. On the other hand, technologies (e.g., machine learning, foundation models, the internet of things) are increasing the capacity for centralized surveillance, the ability of small groups of engineers to set patterns in systems that shape the rules of social life for billions of citizens and customers and reduce the scope for people to meaningfully participate in shaping their lives and communities. We will call these threats “centralizing”. Both threats strike at the heart of democracy, which, as Alexis de Tocqueville famously highlighted in Democracy in America, depends on deep and diverse, non-market, decentralized social and civil connections to thrive[^Tocqueville].

@@ -25,17 +25,18 @@ The antisocial threat from recent technologies has social, economic, legal, poli

- Socially, there is growing evidence that while social media have offered powerful new platforms for those who have previously been socially isolated (e.g., sexual or religious minorities in conservative locales) to forge connections, on average these tools have contributed to exacerbating social isolation and feelings of exclusion[^OutInTheCountry].

-- Economically, the geographic, temporal and multiemployer flexibility facilitated by the internet and increasingly by telecommuting have expanded opportunity for many workers in developing countries or who fit poorly in traditional labor markets. Yet they have largely been unmatched by the emergence of appropriate labor market institutions (such as unions and labor regulations) that allow workers to share in the potential benefits of these arrangements, . Thus, tending to raise workplace precarity and contribute to the “hollowing-out” of the middle class in many developed countries[^GhostWork].

+- Economically, the geographic, temporal and multiemployer flexibility facilitated by the internet and increasingly by telecommuting have expanded opportunities for many workers in developing countries or who fit poorly in traditional labor markets. Yet they have largely been unmatched by the emergence of appropriate labor market institutions (such as unions and labor regulations) that allow workers to share in the potential benefits of these arrangements, . Thus, tending to raise workplace precarity and contribute to the “hollowing-out” of the middle class in many developed countries[^GhostWork].

- Politically, polarization and the influence of extremist parties has been steadily rising in many developed democracies. While the role of the internet-based social media landscape is a topic of significant academic debate, recent surveys suggest that these tools have fallen far short of their promise of strengthening social and political bonds across differences and may well have contributed to the secular rise in polarization since 2000, especially in the United States[^PolarizationResearch].

- Legally, the proliferation of financial innovation in the past few decades has led to limited measurable consumer benefits (in terms of risk reduction, capital allocation or access to credit) while increasing risk in much of the financial system and proliferating financial instruments. Hence, challenging or even skirting existing regulatory regimes intended to mitigate these harms[^FinancialInnovation]. While innovations surrounding housing finance leading up to the 2008 financial crisis were some of the most impactful examples, perhaps the most extreme (if more contained) case has been the recent activity around digital “crypto” assets and currencies. Given their mismatch for existing regulatory regimes, they have offered pervasive opportunities for speculation, gambling, fraud, regulatory and tax evasion, and other anti-social activities[^CryptoChallenges].

-- Existentially, there is growing concern that the fragmentation of the social sensemaking and collective action capacity is dangerous in the face of the increasing sophistication of technologies of mass destruction ranging from environmental devastation (e.g., climate change, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification) to more direct weapons (e.g., misaligned artificial intelligences, bioweapons)[^TechnologySocietyImpact].Yet even as technology is seen to erode the cohesion of democratic societies, it is also increasingly seen to threaten democracy by strengthening the control of governments and centralizing power in the hands of a small group of private actors.

+- Existentially, there is growing concern that the fragmentation of the social sensemaking and collective action capacity is dangerous in the face of the increasing sophistication of technologies of mass destruction with impact ranging from environmental devastation (e.g., climate change, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification) to the potentially apocalyptic disruptions of more direct weapons (e.g., misaligned artificial intelligence and bioweapons)[^TechnologySocietyImpact].Yet even as technology is seen to erode the cohesion of democratic societies, it is also increasingly seen to threaten democracy by strengthening the control of governments and centralizing power in the hands of a small group of private actors.

- Socially, perhaps the most consistent effect of information technology has been to expand the availability and accelerate the spread of information. This has dramatically eroded the sphere of private life, making an increasing range of information publicly available. While such transparency might in principle have a range of social effects, the power to process and make sense of such information has increasingly concentrated in the hands of corporations and firms that have a combination of privileged access to the information and the capital to invest in large scale statistical models (viz. “AI”) to make these data actionable. Furthermore, because these models improve greatly with access to more data and capital, societies where central actors have access to very large pools of both have tended to pull ahead in the perceived “AI race”, putting pressure on all societies to allow such concentration of informational power to compete[^SurveillanceCapitalism]. Together, these forces have normalized unprecedented systems of surveillance and centralized control over information flow.

- Legally, the speed and transformative power of recent advances in AI have overwhelmed core rights of many democratic societies, leaving critical choices in the hands of restricted groups of engineers from similar social backgrounds. Intellectual property law and other protections of creative activity have been largely obviated by the capacity of large AI models to “remix and replace” content; privacy regimes have failed to keep up with the explosive spread of information; discrimination law is woefully unsuited to address issues raised by the potential emergent biases of black box AI systems. The engineers who could potentially address these issues, on the other hand, typically work for profit-seeking companies or the defense sector, come overwhelmingly from a very specific educational and demographic background (typically white or Asian, male, atheist, highly educated, etc.). This has challenged the core tenets of democratic legal regimes that aim to represent the will of the broad society they govern[^AIChallenges].

- Economically, there is growing evidence that AI and the related broader tendency of information technology since the mid-1980s to replace rather than complement (especially low-educated) human labor has been a central factor in the dramatic rise in the share of income accruing to capital (rather than labor) in past decades and thereby has been a core cause of increased income inequality in developed countries.[^AIandInequality] A rise in market power, mark-ups and (less consistently) industrial concentration around the world has accompanied this decline in labor’s share, particularly in countries and sectors that have most heavily adopted information technology[^MarketPower].

-- Politically and geopolitically, the above forces have strengthened the hand of authoritarian regimes and political movements against democratic countries. Creating both the tools and incentives for mass surveillance, AI, and other large-scale data processing tools, have made it easier for governments to directly maintain censorship and social control. Indirectly, by concentrating economic power and the levers of social control in a small set of (often corporate) choke points, the increase in capital income and market power and the increasing authority of small groups of engineers have made it easier for authoritarian regimes to manipulate or seize the “commanding heights” of the economy and society when they wish[^AuthoritarianTech].

+ Politically and geopolitically, the above forces have strengthened authoritarian regimes and political movements against democratic countries. Creating both the tools and incentives for mass surveillance, AI, and other large-scale data processing tools, has made it easier for governments to directly maintain censorship and social control. Indirectly, by concentrating economic power and the levers of social control in a small set of (often corporate) choke points, the increase in capital income and market power and the increasing authority of small groups of engineers have made it easier for authoritarian regimes to manipulate or seize the “commanding heights” of the economy and society when they wish[^AuthoritarianTech].

Furthermore, these two threats intersect; authoritarian regimes have increasingly harnessed the “chaos” of social media and cryptocurrencies to sow internal division and conflict in democratic countries. Centralized social media platforms have leveraged AI to optimize user engagement with their services, often helping to fuel the centrifugal tendencies of misinformation and opinion clustering. Yet, even when they are not actively complementing each other and may in many ways have opposite philosophies, both forces have pressured democratic societies and helped undermine confidence in them, confidence that is now at its lowest ebb in much of the developed democratic world since it has been measured.

+Ironically, in fragile democracies where the state has limited capacity for technology governance, chaos (the collapse of the prevailing order through disruptive technologies) could be an ally of democracy. From the Arab Spring that swept across North Africa in the early 2010s to Nigeria's #EndSARS movement in 2020, autocracies and fragile democracies have recorded the rise of an emerging class of social media-savvy, financial technology (fintech)-enabled and cryptocurrency-empowered class of young citizens deploying these technologies to challenge authoritarian state institutions. These disruptors have been aided by the algorithms of the technology companies, albeit to the extent that the objectives of such social movements align with the commercial interests of the corporations[[^SocialMovements]]([url](https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1350508420961532)). In some cases, such movements have been boosted by the explicit endorsement and backing of the influential founder[[^JackDorsey]]([url](https://www.thecable.ng/fact-check-did-twitter-fund-endsars-protests-as-lai-claimed)). Without a doubt, such interventions foster democratic movements and amplify the otherwise repressed voices of citizens. However, aside from the risk of poor understanding of context and potential divisiveness that such foreign interventions could be prone to[[^TwitterEndSARS]]([url](https://slate.com/technology/2021/04/endsars-nigeria-twitter-jack-dorsey-feminist-coalition.html)), they underscore the debate around the impact of non-state actors such as the global corporation on state sovereignty in Africa and the global South by extension.

### Democracies’ Hostility to Technology

@@ -44,8 +45,7 @@ Yet the hostilities have been far from unidirectional. Democracies have, by and

This failure has manifested in four ways. First, public opinion in democratic countries and their policy-makers are increasingly hostile to large technology companies and even many technologists, a trend commonly called the “techlash”. Second, democratic countries have significantly reduced their direct investment in the development of information technology. Third, democratic countries have been slow to adopt technology in public sector applications or that require significant public sector participation. Finally, and relatedly, democratic governments have largely failed to address the areas where most technologists believe public participation, regulation, and support are critical to technology advancing in a sustainable way, focusing instead on more historically grounded social and political problems[^DemocracyTechHostility].

-Public and policymaker attitudes towards technology took a decidedly negative turn during the 2010s. While at the end of the 2000s and early 2010s, social media and the internet were seen as forces for openness and participation, in the late 2010s they were widely blamed in commentary and to a lesser extent in public opinion surveys for many of the ills listed above [^PublicOpinionTech].This shift in attitudes has perhaps been most clearly reflected in elite attitudes, with best-selling books on technology, such as Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil and *The Age of Surveillance Capitalism* by Shoshanna Zuboff and films like The Social Dilemma, dominating the public conversation and political leaders across the spectrum (e.g., Jeremy Corbyn on the left and Josh Hawley on the right) taking and increasingly pessimistic and aggressive tone on the technology industry. The “Techlash” rose to prominence to describe these concerns. This has been reinforced by the rise of a “cancel culture” that often harnesses social media to attack or reduce the cultural currency of prominent figures and has frequently targeted leaders in the technology industry.

-

+Public and policymaker attitudes towards technology took a decidedly negative turn during the 2010s. While at the end of the 2000s and early 2010s, social media and the internet were seen as forces for openness and participation, in the late 2010s they were widely blamed in commentary and to a lesser extent in public opinion surveys for many of the ills listed above [^PublicOpinionTech].This shift in attitudes has perhaps been most clearly reflected in elite attitudes, with best-selling books on technology, such as Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil and *The Age of Surveillance Capitalism* by Shoshanna Zuboff and films like The Social Dilemma, dominating the public conversation and political leaders across the spectrum (e.g., Jeremy Corbyn on the left and Josh Hawley on the right) taking an increasingly pessimistic and aggressive tone on the technology industry. The “Techlash” rose to prominence to describe these concerns. This has been reinforced by the rise of a “cancel culture” that often harnesses social media to attack or reduce the cultural currency of prominent figures and has frequently targeted leaders in the technology industry.

Regulators in both Europe and the United States have responded with a range of actions, including dramatically increased antitrust scrutiny of leading technology companies, a series of regulatory interventions in Europe including the General Data Protection Regulation and the trio of the Data Governance Act, the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act. All these actions have clear policy rationales and could well be part of a positive technology agenda. However, the combination of negative tone, relative disconnection from naturally allied developments in technology and general reticence on the part of commentators and policy-makers in developed democracies to articulate a positive technology vision has created an impression of an industry under siege.

@@ -58,20 +58,19 @@ Beyond this quantitative story, the declining appearance of public support for i

While the original internet was almost entirely developed by the public and academic sectors and based on open standards, Web 2.0 and the recent movements around “Web 3” and decentralized social technologies have received virtually no public support, as governments in democratic countries struggle to explore the potential of digital currencies, payments, and identity systems. While many of the most fundamental advances in computing arose from democratic governments during World War II and the Cold War, today governments have played virtually no role in the breakthroughs in “foundation models” that are revolutionizing computer science. In fact, OpenAI Founders Sam Altman and Elon Musk report having initially sought public funding and only having turned to private, profit-driven sources after being repeatedly turned down; OpenAI went on to develop the Generative Pretrained Transformer (GPT) models that have increasingly captured the public’s imagination about the potential of AI [^AltmanInterview]. Again, this contrasts sharply with authoritarian regimes, like the PRC, that have laid out and to a large extent successfully deployed ambitious public information technology strategies[^TechStrategyPRC].

-This lack of public sector engagement with technology extends beyond research and development to deployment, adoption, and facilitation. The easiest areas to measure this are the quality and availability of digital connectivity and education. Here the data are somewhat mixed, as many high-functioning democracies (such as the Scandinavian countries) have high quality and high availability internet. But it is striking that leading authoritarian regimes dramatically outperform democracies at similar development levels, especially in the latest connectivity technology. For example, according to Speedtest.net, the PRC ranks 16th in internet speeds in the world, while only 72nd in income per head; Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies similarly punch above their weight[^DigitalDisconnect]. Performance on 5G, the latest generation of mobile connectivity, is more dramatic: a range of surveys find Saudi Arabia and the PRC consistently in the top 10 best covered jurisdictions by 5G, far above their income levels.

+This lack of public sector engagement with technology extends beyond research and development to deployment, adoption, and facilitation. The easiest areas to measure this are the quality and availability of digital connectivity and education. Here the data are somewhat mixed, as many high-functioning democracies (such as the Scandinavian countries) have high quality and high availability internet. But it is striking that leading authoritarian regimes dramatically outperform democracies at similar development levels, especially in the latest connectivity technology. For example, according to Speedtest.net, the PRC ranks 16th in internet speeds in the world, while only 72nd in income per head; Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies similarly punch above their weight[^DigitalDisconnect]. Performance on 5G, the latest generation of mobile connectivity, is more dramatic: a range of surveys find Saudi Arabia and the PRC consistently in the top 10 best-covered jurisdictions by 5G, far above their income levels.

-More central to the heart of governmental responsibility in democracies, however, is the digitization of public services. Many middle-income and weathy democracies invest less in e-government compared to authoritarian counterparts. The UN e-government development index (EGDI) is a composite measure of three important dimensions of e-government, namely: provision of online services, telecommunication connectivity, and human capital. In 2022, several authoritarian governments ranked highly, including UAE, 13th, Kazakhstan 28th, and Saudia Arabia 31, ahead of many, democracies incuding notably Canada 32, Italy 37, Brazil 49, and Mexico 62. (_United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. E-Government Knowledge Database, 2022. https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/Data-Center).

+More central to the heart of governmental responsibility in democracies, however, is the digitization of public services. Many middle-income and wealthy democracies invest less in e-government compared to authoritarian counterparts. The UN e-government development index (EGDI) is a composite measure of three important dimensions of e-government, namely: provision of online services, telecommunication connectivity, and human capital. In 2022, several authoritarian governments ranked highly, including UAE (13th), Kazakhstan (28th), and Saudia Arabia (31st), ahead of many, democracies including notably, Canada (32nd), Italy (37th), Brazil (49th), and Mexico (62nd). (_United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. E-Government Knowledge Database, 2022. https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/Data-Center).

-Digitization of conventional public services is perhaps the least ambitious dimension along which one might expect democracies to advance in adopting technology. Technology has redefined what services are relevant and in these novel areas, democratic governments have almost entirely failed to keep up with changing times. Where once government provided postal services and public libraries were the backbone of democratic communication and knowledge circulation, today most communication flows through social media and search engines. Where once most public gatherings took place in parks and literal public squares, today it is almost a cliché that the public square has moved online. Yet democratic countries have almost entirely ignored the need to provide and support digital public services. While privately-owned Twitter is the target of constant abuse by public figures, its most important competitor, the non-profit Mastodon and the open Activity Pub standard on which it runs have received a paltry few tens of thousands of dollars in public support, running instead on Patreon donations. More broadly, open source software and other commons-based public goods like Wikipedia have become critical public resources in the digital age; yet governments have consistently failed to support them and have even discriminated against them relative to other charities (for example, open source software providers generally cannot be tax-exempt charities). While authoritarian regimes plow ahead with plans for Central Bank Digital Currencies, most democratic countries are only beginning explorations.

+Digitization of conventional public services is perhaps the least ambitious dimension along which one might expect democracies to advance in adopting technology. Technology has redefined what services are relevant and in these novel areas, democratic governments have almost entirely failed to keep up with changing times. Where once government-provided postal services and public libraries were the backbone of democratic communication and knowledge circulation, today most communication flows through social media and search engines. Where once most public gatherings took place in parks and literal public squares, today it is almost a cliché that the public square has moved online. Yet democratic countries have almost entirely ignored the need to provide and support digital public services. While privately-owned Twitter is the target of constant abuse by public figures, its most important competitor, the non-profit Mastodon and the open Activity Pub standard on which it runs have received a paltry few tens of thousands of dollars in public support, running instead on Patreon donations. More broadly, open source software and other commons-based public goods like Wikipedia have become critical public resources in the digital age; yet governments have consistently failed to support them and have even discriminated against them relative to other charities (for example, open source software providers generally cannot be tax-exempt charities). While authoritarian regimes plow ahead with plans for Central Bank Digital Currencies, most democratic countries are only beginning explorations.

-Most ambitiously, democracies could, as so many autocracies have been doing, help facilitate radical experiments with how technologies could reshape social structures. Yet, here again, democracy seems so often to stand in the way rather than facilitate such experimentation. The PRC government has built cities and reimagined regulations to facilitate driverless cars, such as Shenzhen, and has more broadly built a detailed national technology strategy covering nearly ever aspect of policy, regulation and investment[^TechInvestmentPRC]. Saudi Arabia is busy building a new smart city in the dessert, Neom, to show case a range of green and smart city technology, while even the most modest localized projects in democratic countries, such as Google’s Sidewalk Labs, have been swamped by local opposition.

+Most ambitiously, democracies could, as so many autocracies have been doing, help facilitate radical experiments with how technologies could reshape social structures. Yet, here again, democracy seems so often to stand in the way rather than facilitate such experimentation. The PRC government has built cities and reimagined regulations to facilitate driverless cars, such as Shenzhen, and has more broadly built a detailed national technology strategy covering nearly every aspect of policy, regulation and investment[^TechInvestmentPRC]. Saudi Arabia is busy building a new smart city in the desert, Neom, to showcase a range of green and smart city technology, while even the most modest localized projects in democratic countries, such as Google’s Sidewalk Labs, have been swamped by local opposition.

-Even when it comes to areas where technologists agree regulation and caution are critical, democracies are falling further and further behind the needs of the industry to find solutions to emerging social challenges. There is a growing consensus among technologists that a range of emerging technologies may pose catastrophic or even existential risks that will be hard to prevent after they start to emerge. Examples include artificial intelligence systems that could rapidly self-improve their capacities, cryptocurrencies that could pose systemic financial risks, and the development of highly contagious bioweapons. They regularly bemoan the failure of democratic governments to even contemplate much less plan to confront such risks. Yet, beyond these catastrophic possibilities, a whole range of new technologies require regulatory change to be sustainable.. Labor law misfits geographically and temporally flexible work empowered by technology. Copyright is far too rigid to deal with the attribution of value to data inputs to large AI models. Blockchains are empowering new forms of corporate governance that securities laws struggle to make sense of and are often put into legal jeopardy.

+Even when it comes to areas where technologists agree regulation and caution are critical, democracies are falling further and further behind the needs of the industry to find solutions to emerging social challenges. There is a growing consensus among technologists that a range of emerging technologies may pose catastrophic or even existential risks that will be hard to prevent after they start to emerge. Examples include artificial intelligence systems that could rapidly self-improve their capacities, cryptocurrencies that could pose systemic financial risks, and the development of highly contagious bioweapons. They regularly bemoan the failure of democratic governments to even contemplate much less plan to confront such risks. Yet, beyond these catastrophic possibilities, a whole range of new technologies require regulatory change to be sustainable. Labor law misfits geographically and temporally flexible work empowered by technology. Copyright is far too rigid to deal with the attribution of value to data inputs to large AI models. Blockchains are empowering new forms of corporate governance that securities laws struggle to make sense of and are often put into legal jeopardy.

Yet while bold experiments with new visions of the public sector are more common in autocracies, there is an element far more fundamental to democracy itself in which it has fallen farthest behind the times: the mechanisms of public consent, participation, and legitimation, including voting, petitioning, soliciting of citizen feedback and so forth are perhaps more frozen in the past than any other aspect of democratic societies. Voting in nearly all democracies occurs for major offices once every several years according to rules and technologies that have been largely unchanged for a century. While citizens communicate instantaneously across the planet, they are represented in largely fixed geographic configurations at great expense with low fidelity. Few modern tools of communication or data analysis are regular parts of the democratic lives of citizens.

-At the same time, autocracies have increasingly richly harnessed the latest digital innovations to empower their regimes of surveillance (for good and ill) and social control. For example, the PRC government has widely used facial recognition to monitor population movements, has encouraged the adoption of its Digital Yuan and other surveilled digital payments (which cracking down on more private alternatives) to facilitate financial surveillance and even worked on developing a comprehensive “social credit score” that would track a wide range of citizen activities and condense them to a single and widely-consequential “rating”[^SingleRating]. For several years, the Russian government has been using facial recognition to determine who is participating in protests and detain them after the fact, allowing it to remove dissenters on a large scale with much lower risks to the regime or its police forces[^RussianDigitalControl]. These techniques have intensified and have also been used to enforce war conscription[^RussianDraftEvaders] since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

-

+At the same time, autocracies have increasingly richly harnessed the latest digital innovations to empower their regimes of surveillance (for good and ill) and social control. For example, the PRC government has widely used facial recognition to monitor population movements, has encouraged the adoption of its Digital Yuan and other surveilled digital payments (while cracking down on more private alternatives) to facilitate financial surveillance, and has even worked on developing a comprehensive “social credit score” that would track a wide range of citizen activities and condense them to a single and widely-consequential “rating”[^SingleRating]. For several years, the Russian government has been using facial recognition to determine who is participating in protests and detain them after the fact, allowing it to remove dissenters on a large scale with much lower risks to the regime or its police forces[^RussianDigitalControl]. These techniques have intensified and have also been used to enforce war conscription[^RussianDraftEvaders] since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

In some sense, democracy is being left behind by technology as much by its neglect of technology, compared to many authoritarian states' eager willingness to embrace it for their own ends, as by any anti-democratic tendencies of technology itself.

### You Get What You Pay For

@@ -80,20 +79,20 @@ How did we end up here? Are these conflicts the natural course of technology and

A range of work suggests that technology and democracy could co-evolve in a diversity of ways and that the path we are on is a result of collective choices we’ve made through policies, attitudes, expectations, and culture. The range of possibilities can be seen through a variety of lenses, from science fiction to real-world cases.

-Science fiction shows the astonishing range of futures the human mind is capable of imagining. In many cases, these imaginings are the foundation of many of the technologies that researchers and entrepreneurs end up developing. Some of these correspond to the directions we have seen technology take recently. In his 1992 classic, Snow Crash, Neal Stephenson imagines a future where most people have retreated to live much of their lives in an immersive “metaverse”. In the process they undermine the engagement necessary to support real-world communities, governments, and the like, making space for mafias and cult leaders to rule and develop weapons of mass destruction. This future closely corresponds to elements of the “antisocial” threats to Democracy from Technology we discuss above and other writing by Stephenson further extends these possibilities, which have had a profound effect in shaping technology development; for example, Meta’s Platforms is named after Stephenson’s metaverse. Similar examples are possible for the tendency of technology to concentrate power through creating “superintelligences”. Leading examples are the fiction of Isaac Asimov and Ian Banks, the predictive futurism of Ray Kurzweil, and films like Terminator and Her.

+Science fiction shows the astonishing range of futures the human mind is capable of imagining. In many cases, these imaginings are the foundation of many of the technologies that researchers and entrepreneurs end up developing. Some of these correspond to the directions we have seen technology take recently. In his 1992 classic, Snow Crash, Neal Stephenson imagines a future where most people have retreated to live much of their lives in an immersive “metaverse”. In the process they undermine the engagement necessary to support real-world communities, governments, and the like, making space for mafias and cult leaders to rule and develop weapons of mass destruction. This future closely corresponds to elements of the “antisocial” threats to Democracy from Technology we discussed above. Stephenson and other writers further extend these possibilities, which have had a profound effect in shaping technology development; for example, Meta’s Platforms is named after Stephenson’s metaverse. Similar examples are possible for the tendency of technology to concentrate power through creating “superintelligences”. Leading examples are the fiction of Isaac Asimov and Ian Banks, the predictive futurism of Ray Kurzweil, and films like Terminator and Her.

-But these possibilities are both very different from each other and are far from the only visions of the technological future to be found in sci-fi. In fact, some of the most prominent science fiction shows very different possibilities. Two of the most popular sci-fi television shows of all time, The Jetsons and Star Trek show futures where, respectively, technology has largely reinforced the culture and institutions of 1950s America and one where it has enabled a post-capitalist world of diverse intersecting alien intelligences. But these are two among thousands of examples, from the post-gender and post-state imagination of Urusula LeGuin to the post-colonial futurism of Octavia Butler. All suggest a dizzying range of ways technology could coevolve with society[^ScienceFiction].

+But these possibilities are both very different from each other and are far from the only visions of the technological future to be found in sci-fi. In fact, some of the most prominent science fiction shows very different possibilities. Two of the most popular sci-fi television shows of all time, The Jetsons and Star Trek, show futures where, respectively, technology has largely reinforced the culture and institutions of 1950s America and one where it has enabled a post-capitalist world of diverse intersecting alien intelligences. But these are two among thousands of examples, from the post-gender and post-state imagination of Ursula Le Guin to the post-colonial futurism of Octavia Butler. All suggest a dizzying range of ways technology could coevolve with society[^ScienceFiction].

-But science fiction writers are not alone. The primary theme of the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS), including the philosophy, sociology, and history of science, has been the contingency and possibility inherent in the development of science and technology and the lack of any single necessary direction for their evolution[^STS]. These conclusions have been increasingly accepted in social sciences, like political science and economics, that traditionally viewed technology progress as fixed and given. Two of the world’s leading economists, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, have recently published a book arguing that the direction of technological progress is a key target for social policy and reform and documenting the historical contingencies that led to the directions of technology we have seen in the past[^PowerProgress].

+But science fiction writers are not alone. The primary theme of the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS), including the philosophy, sociology, and history of science, has been the contingency and possibility inherent in the development of science and technology and the lack of any single necessary direction for their evolution[^STS]. These conclusions have been increasingly accepted in social sciences, like political science and economics, that traditionally viewed technology progress as fixed and given. Two of the world’s leading economists, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, have recently published a book that argues that the direction of technological progress is a key target for social policy and reform while documenting the historical contingencies that led to the directions of technology we have seen in the past[^PowerProgress].

-Perhaps the most striking illustration comes from comparing the ways technology has advanced across countries today. Where once leading thinkers predicted the power of technology to sweep away social differences, today the technological systems of powers great and sometimes small define their competing social systems as much as their formally stated ideologies: the PRC surveillance regime looks like one technological future, while the Russian hacking networks seem another, the growing space of Web3 driven communities a third, the mainstream Western capitalist countries on which we have focused a fourth and the heterogeneous digital democracies of India, Estonia, and Taiwan something else entirely that we will explore in depth below. Far from converging, technology seems to be proliferating possible futures.

+Perhaps the most striking illustration comes from comparing the ways technology has advanced across countries today. Where once leading thinkers predicted the power of technology to sweep away social differences, today the technological systems of powers great and sometimes small define their competing social systems as much as their formally stated ideologies: the PRC surveillance regime looks like one technological future, while the Russian hacking networks seem another, the growing space of Web3 driven communities a third, the mainstream Western capitalist countries on which we have focused a fourth and the heterogeneous digital democracies of India, Estonia, and Taiwan something else entirely that we will explore in depth below. Also possible, largely along the Web3 community-driven approach, is an African model that could be built on open source and interoperability, reflective of the communal inclination of many African cultures. Far from converging, technology seems to be proliferating possible futures.

So, if our current trajectory of technology and social relationship to it in Western liberal democracies is not inevitable, in what ways are we choosing to be on this conflictual path? And how might we get off it?

-While there are many ways to describe the choices democratic societies have made about technology, perhaps the most concrete and easiest to quantify are the investment realized. These show clear choices about technological paths that Western liberal democracies (and thus most of the financial capital in the world) have made about investments in the future of technology, many of a quite recent origin. While these have recently been driven primarily by the private sector, they reflect earlier priorities set by governments that are in many ways just beginning to filter through to private sector applications.

+While there are many ways to describe the choices democratic societies have made about technology, perhaps the most concrete and easiest to quantify are the investments realized. These show clear choices about technological paths that Western liberal democracies (and thus most of the financial capital in the world) have made about investments in the future of technology, many are of quite recent origin. While these have recently been driven primarily by the private sector, they reflect earlier priorities set by governments that are in many ways just beginning to filter through to private sector applications.

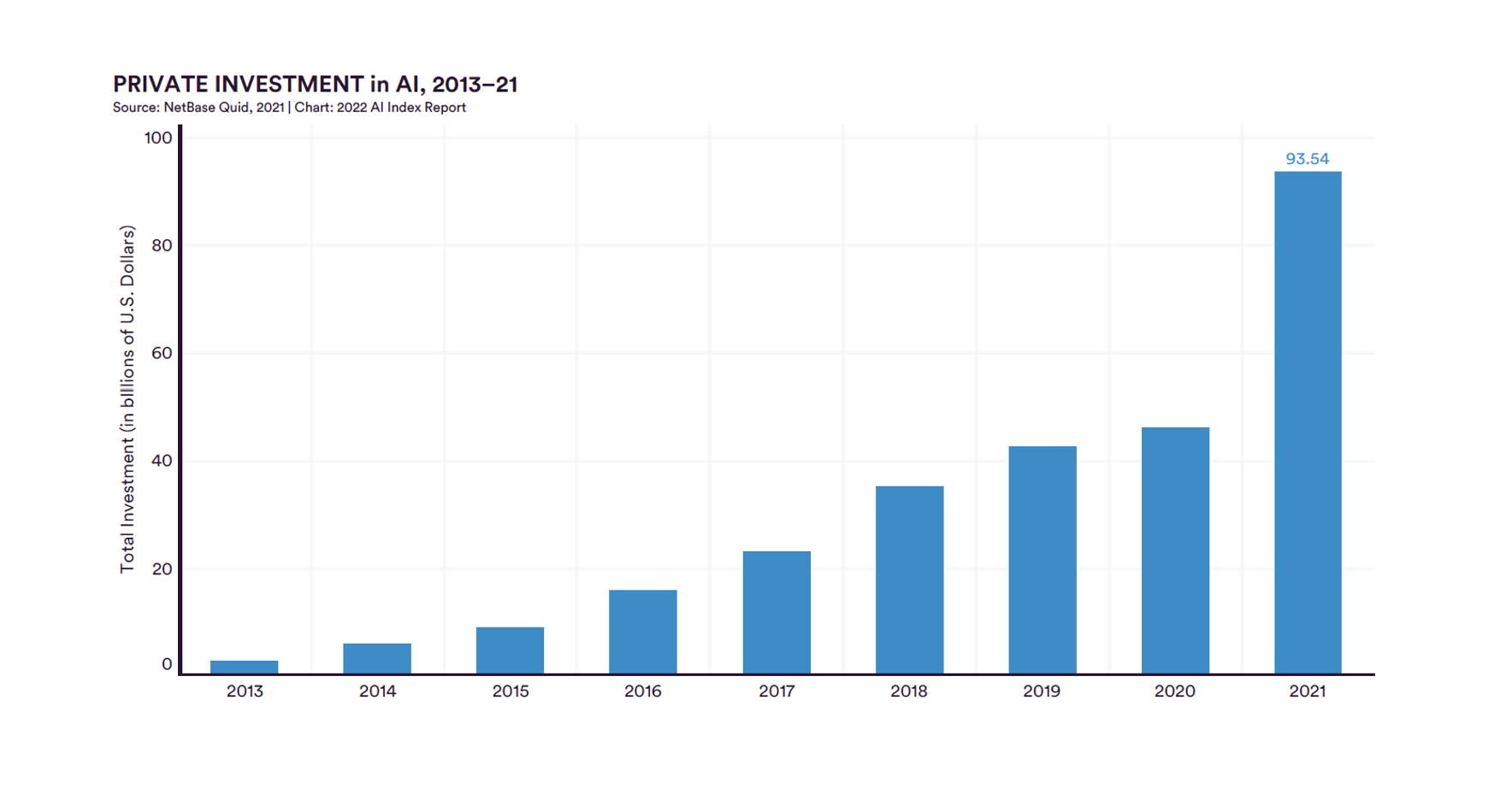

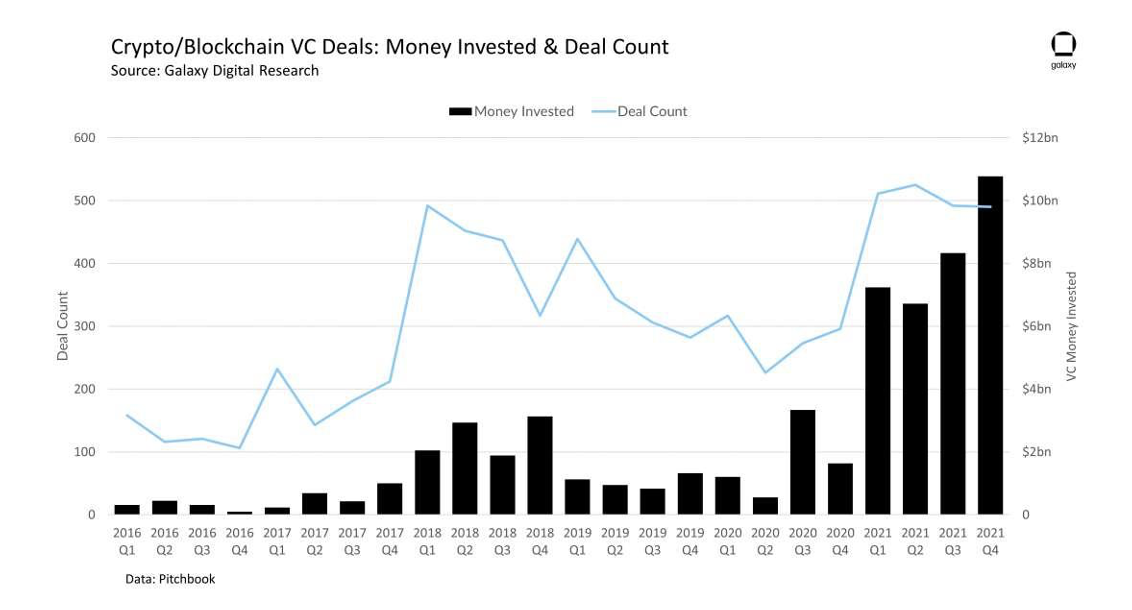

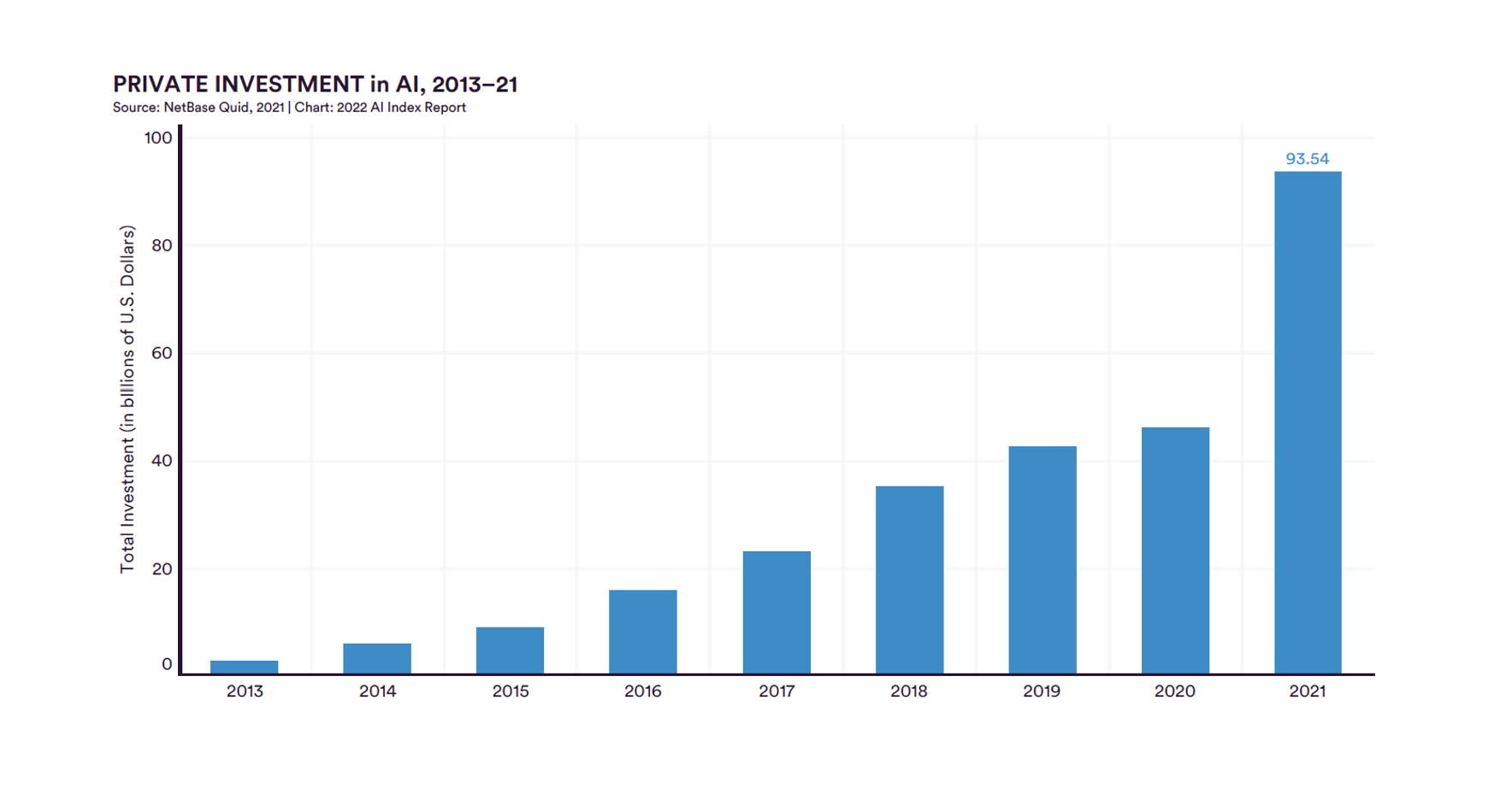

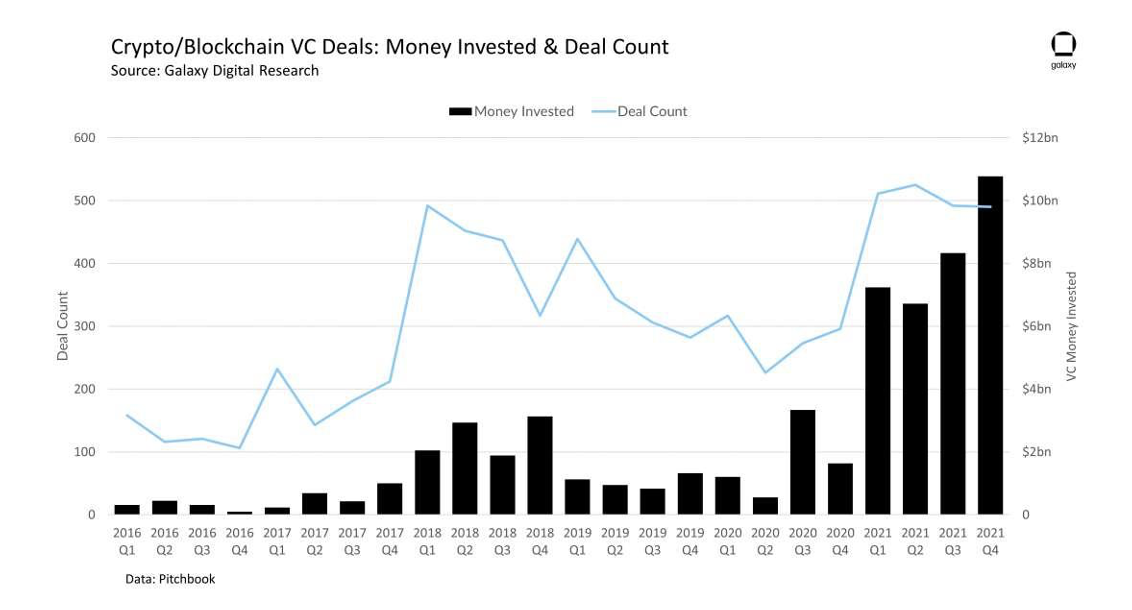

-Beginning with recent trends in the increasingly well-measured venture capital industry, the last decade has seen a dramatic and overwhelming focus of venture capital within the high technology sector into artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency-adjacent/“Web3” technologies. Figure V displays data on private investment in AI collected by NetBase Quid and charted by the Stanford’s Center for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence’s 2022 AI Index Report, showing its explosive growth over the course of the 2010s, growth that has come to dominate private technology investment; Figure W show the same (over a different time period and quarterly) for the Web3 space based on data from Pitchbook, graphed by Galaxy Digital Research.

+Beginning with recent trends in the increasingly well-measured venture capital industry, the last decade has seen a dramatic and overwhelming focus of venture capital within the high technology sector into artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency-adjacent/“Web3” technologies. Figure V displays data on private investment in AI collected by NetBase Quid and charted by Stanford’s Center for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence’s 2022 AI Index Report, showing its explosive growth over the course of the 2010s, growth that has come to dominate private technology investment; Figure W shows the same (over a different period and quarterly) for the Web3 space based on data from Pitchbook, graphed by Galaxy Digital Research.

@@ -104,8 +103,11 @@ However, while these priorities are relatively recent and appear to emerge from

These investments are not just choices that could have been made differently; they are quite recent and were made very differently immediately prior. These investments are reflected in the canonical technologies of the last few decades. Artificial intelligence was heralded as a coming revolution throughout much of the 1980s, as reflected in FIGURE HERE FROM GOOGLE NGRAMS showing the relative frequency of this phrase in English books as tracked by Google nGrams, Yet the defining technology of the 1980s was quite opposite: the personal computer that made computing a complement to individual human creativity. The 1990s were haunted by Stephenson’s science fictional imagination of the possibilities of escapist virtual worlds and atomizing cryptography, the connective tissue of the internet swept the world, ushering in an unprecedented age of communication and cooperation. Mobile telephony in the 2000s, social networking in the 2010s, and the scaffolding of remote work in the 2020s…none of these have focused on either cryptographic hypercapitalism or artificial superintelligence.

-This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Departments Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+

+### Geopolitics and the Evolution of Technology and Democracy

+There is a definite geopolitical context to the disposition of democracies to technology. Research on the evolution of innovation over history and time suggests that the changing attitudes of Western democracies to public technology investment have been moderated by geopolitical competitive pressures from eastward autocratic rivals[[^NavigatingtheGeopoliticsofInnovation]]([url](https://remakeafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Navigating_the_Geopolitics_of_Innovation.pdf)). In the United States, for instance, the first and second phases of the innovation age (Industry 1.0 and Industry 2.0 respectively) which featured the emergence of such technologies as the steam engine, rail transport, the telegraph, and the assembly line were driven by the private sector in a relatively less intense geopolitical context in the pre-War era, an era of relative American isolation from global politics. However, the third phase (Industry 3.0), enabled by such technologies as semiconductors and the Internet, occurred in the context of intense geopolitics – the Cold War. Thus, driven by geopolitical exigencies, the 20th-century innovations were led by the government through such national institutional frameworks as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) as well as regional alliances of democracies such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent collapse of an autocratic adversary, the geopolitical drivers of innovation waned in intensity, leading to a reduction in incentives for public investments in technology. About three decades later, the rise of China as a formidable challenger to the West’s innovation leadership and the resurgence of an empire-seeking Russia have reawakened the United States and other Western democracies to the urgency of innovation leadership in an era of exponential technologies loosely described as the fourth industrial revolution or Industry 4.0. Hence, we see such recent, somewhat corrective, public spending by the United States government through such institutional mechanisms as the National Science Foundation to bolster America's leadership in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence [[^WhiteHouse2024Budget]]([url](https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2023/03/13/fy24-budget-fact-sheet-rd-innovation/)). This geopolitically driven attitude of the United States towards technology investment - an attitude that is reactive or proactive to the presence or otherwise of a rising or formidable adversary - leans towards what was described by Robert Atkinson as “digital realpolitik”[[^RobertAtkinson]]([url](https://www2.itif.org/2021-us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy.pdf)).

### Ideologies of the Twenty-First Century

@@ -104,8 +103,11 @@ However, while these priorities are relatively recent and appear to emerge from

These investments are not just choices that could have been made differently; they are quite recent and were made very differently immediately prior. These investments are reflected in the canonical technologies of the last few decades. Artificial intelligence was heralded as a coming revolution throughout much of the 1980s, as reflected in FIGURE HERE FROM GOOGLE NGRAMS showing the relative frequency of this phrase in English books as tracked by Google nGrams, Yet the defining technology of the 1980s was quite opposite: the personal computer that made computing a complement to individual human creativity. The 1990s were haunted by Stephenson’s science fictional imagination of the possibilities of escapist virtual worlds and atomizing cryptography, the connective tissue of the internet swept the world, ushering in an unprecedented age of communication and cooperation. Mobile telephony in the 2000s, social networking in the 2010s, and the scaffolding of remote work in the 2020s…none of these have focused on either cryptographic hypercapitalism or artificial superintelligence.

-This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Departments Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+

+### Geopolitics and the Evolution of Technology and Democracy

+There is a definite geopolitical context to the disposition of democracies to technology. Research on the evolution of innovation over history and time suggests that the changing attitudes of Western democracies to public technology investment have been moderated by geopolitical competitive pressures from eastward autocratic rivals[[^NavigatingtheGeopoliticsofInnovation]]([url](https://remakeafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Navigating_the_Geopolitics_of_Innovation.pdf)). In the United States, for instance, the first and second phases of the innovation age (Industry 1.0 and Industry 2.0 respectively) which featured the emergence of such technologies as the steam engine, rail transport, the telegraph, and the assembly line were driven by the private sector in a relatively less intense geopolitical context in the pre-War era, an era of relative American isolation from global politics. However, the third phase (Industry 3.0), enabled by such technologies as semiconductors and the Internet, occurred in the context of intense geopolitics – the Cold War. Thus, driven by geopolitical exigencies, the 20th-century innovations were led by the government through such national institutional frameworks as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) as well as regional alliances of democracies such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent collapse of an autocratic adversary, the geopolitical drivers of innovation waned in intensity, leading to a reduction in incentives for public investments in technology. About three decades later, the rise of China as a formidable challenger to the West’s innovation leadership and the resurgence of an empire-seeking Russia have reawakened the United States and other Western democracies to the urgency of innovation leadership in an era of exponential technologies loosely described as the fourth industrial revolution or Industry 4.0. Hence, we see such recent, somewhat corrective, public spending by the United States government through such institutional mechanisms as the National Science Foundation to bolster America's leadership in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence [[^WhiteHouse2024Budget]]([url](https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2023/03/13/fy24-budget-fact-sheet-rd-innovation/)). This geopolitically driven attitude of the United States towards technology investment - an attitude that is reactive or proactive to the presence or otherwise of a rising or formidable adversary - leans towards what was described by Robert Atkinson as “digital realpolitik”[[^RobertAtkinson]]([url](https://www2.itif.org/2021-us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy.pdf)).

### Ideologies of the Twenty-First Century

@@ -104,8 +103,11 @@ However, while these priorities are relatively recent and appear to emerge from

These investments are not just choices that could have been made differently; they are quite recent and were made very differently immediately prior. These investments are reflected in the canonical technologies of the last few decades. Artificial intelligence was heralded as a coming revolution throughout much of the 1980s, as reflected in FIGURE HERE FROM GOOGLE NGRAMS showing the relative frequency of this phrase in English books as tracked by Google nGrams, Yet the defining technology of the 1980s was quite opposite: the personal computer that made computing a complement to individual human creativity. The 1990s were haunted by Stephenson’s science fictional imagination of the possibilities of escapist virtual worlds and atomizing cryptography, the connective tissue of the internet swept the world, ushering in an unprecedented age of communication and cooperation. Mobile telephony in the 2000s, social networking in the 2010s, and the scaffolding of remote work in the 2020s…none of these have focused on either cryptographic hypercapitalism or artificial superintelligence.

-This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Departments Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+

+### Geopolitics and the Evolution of Technology and Democracy

+There is a definite geopolitical context to the disposition of democracies to technology. Research on the evolution of innovation over history and time suggests that the changing attitudes of Western democracies to public technology investment have been moderated by geopolitical competitive pressures from eastward autocratic rivals[[^NavigatingtheGeopoliticsofInnovation]]([url](https://remakeafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Navigating_the_Geopolitics_of_Innovation.pdf)). In the United States, for instance, the first and second phases of the innovation age (Industry 1.0 and Industry 2.0 respectively) which featured the emergence of such technologies as the steam engine, rail transport, the telegraph, and the assembly line were driven by the private sector in a relatively less intense geopolitical context in the pre-War era, an era of relative American isolation from global politics. However, the third phase (Industry 3.0), enabled by such technologies as semiconductors and the Internet, occurred in the context of intense geopolitics – the Cold War. Thus, driven by geopolitical exigencies, the 20th-century innovations were led by the government through such national institutional frameworks as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) as well as regional alliances of democracies such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent collapse of an autocratic adversary, the geopolitical drivers of innovation waned in intensity, leading to a reduction in incentives for public investments in technology. About three decades later, the rise of China as a formidable challenger to the West’s innovation leadership and the resurgence of an empire-seeking Russia have reawakened the United States and other Western democracies to the urgency of innovation leadership in an era of exponential technologies loosely described as the fourth industrial revolution or Industry 4.0. Hence, we see such recent, somewhat corrective, public spending by the United States government through such institutional mechanisms as the National Science Foundation to bolster America's leadership in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence [[^WhiteHouse2024Budget]]([url](https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2023/03/13/fy24-budget-fact-sheet-rd-innovation/)). This geopolitically driven attitude of the United States towards technology investment - an attitude that is reactive or proactive to the presence or otherwise of a rising or formidable adversary - leans towards what was described by Robert Atkinson as “digital realpolitik”[[^RobertAtkinson]]([url](https://www2.itif.org/2021-us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy.pdf)).

### Ideologies of the Twenty-First Century

@@ -104,8 +103,11 @@ However, while these priorities are relatively recent and appear to emerge from

These investments are not just choices that could have been made differently; they are quite recent and were made very differently immediately prior. These investments are reflected in the canonical technologies of the last few decades. Artificial intelligence was heralded as a coming revolution throughout much of the 1980s, as reflected in FIGURE HERE FROM GOOGLE NGRAMS showing the relative frequency of this phrase in English books as tracked by Google nGrams, Yet the defining technology of the 1980s was quite opposite: the personal computer that made computing a complement to individual human creativity. The 1990s were haunted by Stephenson’s science fictional imagination of the possibilities of escapist virtual worlds and atomizing cryptography, the connective tissue of the internet swept the world, ushering in an unprecedented age of communication and cooperation. Mobile telephony in the 2000s, social networking in the 2010s, and the scaffolding of remote work in the 2020s…none of these have focused on either cryptographic hypercapitalism or artificial superintelligence.

-This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Departments Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+This reflects, with an extensive lag, the shift in investments made by public sector research funders. While data are imperfect, W. Mitchell Waldrop documents the shift clearly in his classic The Dream Machine: as the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which funded the ARPANET that grew into the Internet, changed its name to the Defense ARPA (DARPA), it shifted its investment focus as well. It dramatically reduced its focus emphasis on resilient communications and sociotechnical systems and increased its focus on systems viewed as more directly supportive of military aims, including weapons autonomy and cryptography. By 1979, the inaugural ARPA program officer who funded the ARPANET and the world’s first computer science departments, JCR Licklider, was already lamenting the turn of public money away from investments in the critical infrastructure supporting his vision of a network society[^LickliderReflection]. This trend accelerated further during the 1980s, as attention around national defense increasingly narrowed.

+

+### Geopolitics and the Evolution of Technology and Democracy

+There is a definite geopolitical context to the disposition of democracies to technology. Research on the evolution of innovation over history and time suggests that the changing attitudes of Western democracies to public technology investment have been moderated by geopolitical competitive pressures from eastward autocratic rivals[[^NavigatingtheGeopoliticsofInnovation]]([url](https://remakeafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Navigating_the_Geopolitics_of_Innovation.pdf)). In the United States, for instance, the first and second phases of the innovation age (Industry 1.0 and Industry 2.0 respectively) which featured the emergence of such technologies as the steam engine, rail transport, the telegraph, and the assembly line were driven by the private sector in a relatively less intense geopolitical context in the pre-War era, an era of relative American isolation from global politics. However, the third phase (Industry 3.0), enabled by such technologies as semiconductors and the Internet, occurred in the context of intense geopolitics – the Cold War. Thus, driven by geopolitical exigencies, the 20th-century innovations were led by the government through such national institutional frameworks as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) as well as regional alliances of democracies such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent collapse of an autocratic adversary, the geopolitical drivers of innovation waned in intensity, leading to a reduction in incentives for public investments in technology. About three decades later, the rise of China as a formidable challenger to the West’s innovation leadership and the resurgence of an empire-seeking Russia have reawakened the United States and other Western democracies to the urgency of innovation leadership in an era of exponential technologies loosely described as the fourth industrial revolution or Industry 4.0. Hence, we see such recent, somewhat corrective, public spending by the United States government through such institutional mechanisms as the National Science Foundation to bolster America's leadership in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence [[^WhiteHouse2024Budget]]([url](https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2023/03/13/fy24-budget-fact-sheet-rd-innovation/)). This geopolitically driven attitude of the United States towards technology investment - an attitude that is reactive or proactive to the presence or otherwise of a rising or formidable adversary - leans towards what was described by Robert Atkinson as “digital realpolitik”[[^RobertAtkinson]]([url](https://www2.itif.org/2021-us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy.pdf)).

### Ideologies of the Twenty-First Century