Hi, my name is Mikhail Emelyanov, I’m a Python programmer and I would like to show you my pet project — Flywheel, a micro-platform for learning foreign languages, a mixture of Duolingo and Anki, an application that can teach you to properly write in Spanish (or any other language you’re studying). Flywheel’s source code is available on GitHub.

As you may know, generalized knowledge of a foreign language can be broken down into four relatively independent components: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Unfortunately, training one of these abilities has no direct effect on the other components, so, for example, by developing our reading skills, the effect on our writing skills is quite indirect. Flywheel is a ‘sharpener’ specifically for written Spanish.

If you’ve ever used Duolingo, you should have some idea of the format in which you’ll be studying. The formula is simple: here’s a phrase, translate it into the other language; the app will remember the last time you translated a phrase and how successful you were at it; and depending on the accuracy of your answer, it will determine when you should do the same phrase again. In my opinion, Duolingo and its approach are brilliant. However... There are certain aspects that somewhat spoil the learning experience, and Flywheel was specifically designed to address them.

First and most importantly, I want all translation assignments to be English to Spanish only. I only want to see English phrases that I need to translate into Spanish. I don’t want to translate from Spanish to English. I’m not studying to be a translator; I want to learn a foreign language! And in my opinion, the way to do that is to not write anything in English at all while I’m studying. There’s a little lifehack for Duolingo — you can switch from learning Spanish for English speakers to learning English for Spanish speakers (this, in part, explains the large number of students in this course) so that the course will contain more English-to-Spanish assignments, although the amount of Spanish-to-English translations will still be very large. Whereas I want 100 % of the lesson time to be written in Spanish!

Second, I’m an adult, and I don’t need the studying process to be gamified at all. All those little people cheerfully winking, encouraging and advising me is one giant, irrelevant and annoying pain. There are even browser extensions that try to cut out all of these unnecessary functions, reducing the website’s visuals to the necessary level of minimalism.

Third, I’m an adult (yes, I’m repeating myself) and sometimes I don’t have the time for a full-sized lesson. While Duolingo has fairly short ones, the breakdown of the learning process into set lessons containing an XX amount of questions is primarily convenient for the learning platform, not the learner. I want to be able to repeat not twenty phrases, but, say, five or three, or even one. I want to be able to interrupt the studying process at any moment without losing progress! After all, I sometimes am only able to practice on rare breaks of undetermined duration between my main activities over tea and cookies, or during breaks between spending time with the kids. If I have only a literal spare minute, I want to do a couple of sets and maintain my progress.

Fourth, I want to be able to add new phrases at any stage of my study! After hearing or reading something new, useful or just interesting, I want to add the phrase to the list, letting the app ensure that this phrase will remain in my memory forever.

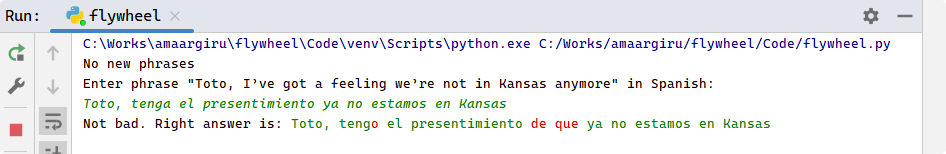

Fifth, but also no less important consideration — I want the program to indicate the wrong parts of the translation. Sometimes the entered text contains small mistakes or typos, catching which is difficult with a naked eye. I want the program to show the difference between my translation and the correct version, so that I can focus on learning Spanish, and not on the game of finding the wrong letter in a long phrase in a foreign language.

This is my wish list — I want Duolingo, but only with English-to-Spanish tasks, without gamification, saving progress after each task, with the ability to add new phrases and with the visualization of the errors made, even minor ones.

I think that’s where the preface can end and we can get to the heart of the matter. If you simply want to start learning Spanish, go to the next section, ‘Usage.’ If you want to see the app’s inner workings, go to the ‘How It Works’ section (near the end of the article).

Using Flywheel is extremely simple. At the start, you have just one file, phrases.txt (the file that comes with the application contains about two thousand phrases). Inside are many pairs of phrases, separated with a double vertical line, e.g.:

I love you || Te quiero

If the English phrase can be correctly translated into several different Spanish phrases, a single vertical line is used to separate them:

I know || Lo se | Ya se | Yo sé

If there are two English phrases that can also have multiple equivalent translations, a single vertical line is also used to separate them.

Of course, you can and should add your own phrase pairs to phrases.txt. This is the essence of Flywheel — you don’t have to memorize the dictionary, it’s just a template. Adjust the content of the lessons to suit your level of proficiency; move the phrase pairs you find most useful higher up in the dictionary; add pairs related to your job. Needless to say, the shell doesn’t care what language you’re learning. If you wish to learn French, bien accueillir! Want to learn Aleutian? No problem. Need to learn Aleutian as a native French speaker? Easy as pie!

Please don’t add single words to the dictionary! Sure, technically it’s possible, but it’s not particularly worthwhile from the perspective of language learning efficiency. Try adding phrases specifically, and if you want to add a specific new word to your vernacular it’s better to pick up a phrase which uses it in a specific context. This way you’ll not only remember the word better, but you’ll more easily move it from the passive phase to the active phase, as you won’t simply recognize it in a text or in speech, but will actually start applying it in writing and in speaking.

Next, simply run flywheel.py. Two more files will be added to your application folder — repetitions.json (this will record your progress and memorization of all completed phrase pairs) and user_statistics.txt (this will record the total number of exercises you have completed and will generate a general list of words you have managed to learn).

If you are a beginner Python developer and want to try your hand at something simple but not useless, give Flywheel a whirl. Maybe you’ll be able to add some hot new features to it, and improve your Spanish while debugging it as well. Naturally, most of the methods used in the application don’t need a lot of describing, so I’ll focus only on the general approach and the key functions that are directly related to the analysis of user progress.

Recently I have been practicing the following method: I write a template main as if all of the application’s methods have already been developed and I just need to call them. This gives you sort of a bird’s-eye view of the code (even if it’s more like a penguin’s rather than an eagle’s :) and a rough estimate of the level of effort required. This is what I ended up with:

phrases_file_name = "phrases.txt"

repetitions_file_name = "repetitions.json"

if __name__ == "__main__":

phrases_file_path = find_or_create_file(phrases_file_name)

repetitions_file_path = find_or_create_file(repetitions_file_name)

phrases = read_phrases(phrases_file_path)

repetitions = read_repetitions(repetitions_file_path)

can_work, error_message = data_assessment(phrases, repetitions)

if can_work:

message = merge(repetitions, phrases)

print(message)

while True:

current_phrase = determine_current_phrase(repetitions)

user_result = user_session(current_phrase)

update_repetitions(repetitions, current_phrase, user_result)

save_repetitions(repetitions_file_path, repetitions)

else:

print(error_message)

exit()The operating logic is roughly thus:

• we look for phrases.txt in the project directories (lots of phrase pairs separated by a dual vertical line, see the ‘Usage’ section for details); if we can’t find it, we create a blank file for future editing by the user;

• similarly, we look for repetitions.json (progress records and memorization degrees of all complete phrase pairs); if not found, we create an empty file;

• we create data structures from the information taken from phrases.txt and repetitions.json, and then evaluate whether we can work with given combination. If phrases.txt is not empty, then okay, we can convert phrase pairs to our internal format and transfer that information to repetitions.json. If repetitions.json is not empty, then also okay, we can work with the information we’ve already accumulated. Both phrases.txt and repetitions.json being empty is not okay, we have nowhere to draw the information we need to work, so we complain about this fact to the user, let them create phrases.txt with at least some minimal content;

• during the loop, we feed a new task to the user, picking the most relevant phrase we need at the moment from the phrase dictionary. If there are phrases that require repetition, we pick them first; if all completed tasks don’t require a refresher right now, we start mixing in new phrases.

• after each task, we update the data in repetitions.json and the user’s statistics, regardless of the quality of the answer.

In the process of writing the code, I divided all the functionality into data_level (sort of the essence of the language practice itself), system_level (functionality that depends on the operating system) and ui_level (methods that determine how to interact with the user), also adding a statistics file showing the total number of attempts made by the user and containing all the Spanish and English words that they learned. The final version turned out to be about the same as the original blueprint, if only a little more spread out:

from data_level import DataOperations as dop

from system_level import FileOperations as fop

from ui_level import UiOperations as uop

phrases_file_name: str = 'phrases.txt'

repetitions_file_name: str = 'repetitions.json'

statistics_file_name: str = 'user_statistics.txt'

if __name__ == '__main__':

phrases_file_path = fop.find_or_create_file(phrases_file_name)

repetitions_file_path = fop.find_or_create_file(repetitions_file_name)

user_statistics_file_path = fop.find_or_create_file(statistics_file_name)

phrases: dict = fop.read_phrases(phrases_file_path)

repetitions: dict = fop.read_json_from_file(repetitions_file_path)

can_work, assesment_error_message = dop.data_assessment(phrases, repetitions)

statistics: dict = fop.read_json_from_file(user_statistics_file_path)

if can_work:

is_merged, merge_message = dop.merge(phrases, repetitions)

print(merge_message)

if is_merged:

fop.save_json_to_file(repetitions_file_path, repetitions)

while True:

current_phrase: str = dop.determine_next_phrase(repetitions)

user_result, best_translation = uop.user_session(current_phrase, repetitions[current_phrase])

dop.update_repetitions(repetitions, current_phrase, user_result)

fop.save_json_to_file(repetitions_file_path, repetitions)

statistics = dop.update_statistics(statistics, current_phrase, best_translation)

fop.save_json_to_file(statistics_file_name, statistics)

else:

print(assesment_error_message)

exit()First we need to determine whether the user answered the given question correctly, allowing for the possible existence of several correct versions of the translation.

# import jellyfish

def find_max_string_similarity(user_input: str, translations: str | List[str]) -> (float, str):

"""Compares user_input against each string in translations"""

max_distance: float = 0

if isinstance(translations, str):

translations = [translations]

best_translation: str = translations[0]

# Cleanup and 'compactify' user input ('I don't know!!!😀' -> 'i dont know')

user_input = DataOperations._compact(DataOperations._cleanup_user_input(user_input).lower())

# 'Compactify' translations

translations = [(t, DataOperations._compact(t.lower())) for t in translations]

for translation, compact_translation in translations:

current_distance = jellyfish.jaro_distance(user_input, compact_translation)

if current_distance > max_distance:

max_distance = current_distance

best_translation = translation

return max_distance, best_translation

def _compact(input_string: str) -> str:

"""Restrict use of all special characters and allow letters and numbers only"""

return ''.join(ch for ch in input_string if ch.isalnum() or ch == ' ')Inside the husk engaged in data transfer, you can see the Jaro distance calculation:

current_distance = jellyfish.jaro_distance()Accordingly, there is an estimate of the accuracy of the user’s answer:

level_excellent: float = 0.99

level_good: float = 0.97

level_mediocre: float = 0.65Come to think of it, maybe the Levenshtein distance would be more appropriate here?

By the way, try turning this:

user_input = DataOperations._compact(DataOperations._cleanup_user_input(user_input).lower())into something like this (I don't mean dropping DataOperations, but rather arranging a pipe for methods like string):

user_input = user_input.lower().cleanup().compact()Unfortunately, adding your own methods to those provided by Python requires either using subclasses or reinventing something like forbiddenfruit (bit dead already) / fishhook (still a little raw). Meanwhile, C# provides this feature out of the box, curses!

The interval repetition algorithm, which, depending on the quality of the answer, decides when a completed phrase will be offered to the user next time, is based on SuperMemo-2:

def _supermemo2(repetition: dict, user_result: float) -> dict:

"""Update next attempt time based on user result"""

if user_result >= DataOperations.level_good: # Correct response

if repetition['repetition_number'] == 0: # + 1 day

repetition['time_to_repeat'] = (datetime.now() + timedelta(days=1)).strftime(datetime_format)

elif repetition['repetition_number'] == 1: # + 6 days

repetition['time_to_repeat'] = (datetime.now() + timedelta(days=6)).strftime(datetime_format)

else: # + (6 * easiness_factor) days

repetition['time_to_repeat'] = (datetime.now()

+ timedelta(days=6 * repetition['easiness_factor'])).strftime(datetime_format)

repetition['repetition_number'] += 1

else: # Incorrect response

repetition['repetition_number'] = 0

repetition['easiness_factor'] = repetition['easiness_factor'] + (

0.1 - (5 - 5 * user_result) * (0.08 + (5 - 5 * user_result) * 0.02))

repetition['easiness_factor'] = max(repetition['easiness_factor'], 1.3)

return repetitionThe SuperMemo family of algorithms has more recent implementations, up to SuperMemo-18. You can move over to using them, repetitions.json stores the last few user attempts specifically for this purpose.

max_attempts_len: int = 10 # Limit for 'Attempts' listWhile you’re at it, try to figure out why, despite the fact that SuperMemo-18 exists, SuperMemo-2 is still actively used, and even the most adventurous developers don’t venture beyond SuperMemo-5 or, at most, a simplified SuperMemo-8. Have a look at A Trainable Spaced Repetition Model for Language Learning, an algorithm published by the developers of Duolingo, which attempts to address the shortcomings of previous approaches. Try to replicate Duolingo’s key functionality, it’s quite feasible.

Next comes the saving of the results; I think there’s no need to dwell on the implementation of this function.

Now that the user’s answer has been weighed and accounted for, we need to show the student not only the correct option, but also the specifics that will help them identify the mistakes. To do this, we will first form a data structure containing information on the difference between the desired and the actual result.

# from dataclasses import dataclass

# from difflib import SequenceMatcher

def find_user_mistakes(user_input: str, reference: str) -> list:

"""Dig for user errors and typos"""

@dataclass

class ComplexPhrase:

phrase_without_punctuation: List[str]

transformation_matrix: List[int]

user_input = DataOperations._cleanup_user_input(user_input).lower()

reference = reference.lower()

correction_map: list[bool] = [True] * len(reference)

complex_reference: ComplexPhrase = ComplexPhrase(phrase_without_punctuation=[], transformation_matrix=[])

# 'Minify' reference phrase and remember transformation shifts

for i, ch in enumerate(reference):

if ch.isalnum() or ch == ' ':

complex_reference.phrase_without_punctuation.append(ch)

complex_reference.transformation_matrix.append(i)

minified_reference: str = ''.join(complex_reference.phrase_without_punctuation)

corr_map: list[bool] = [False] * len(minified_reference)

# Compare cleaned user input and 'minified' reference

seq = SequenceMatcher(lambda ch: not (ch.isalnum() or ch == ' '), user_input, minified_reference)

blocks = seq.get_matching_blocks()

blocks = blocks[:-1] # Last element is a dummy

for _, i, n in blocks:

if n >= 3: # Don't show to the user too short groups of correct letters, perhaps he entered a completely different phrase

for x in range(i, i + n):

corr_map[x] = True

# 'Unminify' reference phrase and restore transformation shifts

for i, corr in enumerate(corr_map):

if corr is False:

correction_map[complex_reference.transformation_matrix[i]] = False

return correction_mapA bit complicated? At a glance, we could have taken a shorter route by directly applying SequenceMatcher to the user’s response and reference phrase, like this.

def find_user_mistakes(user_input: str, reference: str) -> list:

"""Display of user errors"""

seq = SequenceMatcher(None,

"".join(DataOperations._compact(DataOperations._cleanup_user_input(user_input).lower())),

DataOperations._compact(reference.lower()))

blocks = seq.get_matching_blocks()

blocks = blocks[:-1] # Last element is a dummy

corr_map: list = [False] * len(reference)

for _, i, n in blocks:

if n >= 3: # Don't show to the user too short groups of correct letters, perhaps he entered a completely different word

for x in range(i, i + n):

corr_map[x] = True

return corr_mapInstead, we wrap and then unwrap some additional data structure that does not store all the characters from the source text, but remembers which characters are shifted where. What for?

The thing is, one of Duolingo’s key features is that it ignores punctuation and the difference between uppercase and lowercase letters. For example, it’s perfectly acceptable to type ‘hello my name is kitty’ instead of ‘Hello! My name is Kitty,’ and that’s pretty cool. After all, we’re primarily studying the grammar of a foreign language, having already learned the general rules of writing names and punctuation (although Spanish has its own peculiarities), and getting a fail for spelling the name Michael with a lowercase letter would certainly be a huge drawback for the whole user experience.

This is the kind of goodie I wanted to implement in Flywheel as well. That’s why the reference phrase and the user’s answer are first converted into plain text without punctuation and capital letters, then compared, ending with the reference phrase once again unfolded into a full response and shown to the user.

Next, to clearly show the mistakes and typos to the user, we form a full-colour user output, a phrase in which the colour of the character will depend on the correctness of its spelling:

def _print_colored_diff(correction, reference) -> None:

"""Visualisation of user errors"""

for i, ch in enumerate(reference):

if correction[i]:

print(Fore.GREEN + ch, end='')

else:

if ch != ' ':

print(Fore.RED + ch, end='') # Just a letter

else:

if i - 1 >= 0 and i + 1 < len(reference): # Emphasise the space between correct but sticky characters

if correction[i - 1] and correction[i + 1]:

print(Fore.RED + '_', end='')

else:

print(Fore.RED + ' ', end='')This ends the life cycle of the question in the console application.

Want something like that, but more sophisticated (because making the user quit the application using Ctrl-C is kind of gross), with a web interface, database, ORM, API, and voice prompts? Have a look in the flywheel/Legacy folder. It contains some working code that differs from the latest micro-version described in this article by having a less consistent data_level (in particular, not knowing about SuperMemo, I tried to invent my own algorithm of interval repetitions), but it has all of the aforementioned goodies. Perhaps you’ll hear the quiet one-handed clap calling you back to the console later... Meanwhile, you can try to make your own startup, building a potential rival to Duolingo, Cerego, Course Hero or Memrise.

Well, that’s about it for now. From now until the end of your current lifecycle, you can spend as much time on learning a foreign language as you like, add new phrases or add to existing translations and keep up with your progress even after minuscule efforts.

However, keep in mind that:

• first of all, miracles are not real, and you will have to spend a considerable amount of time (approximate estimates) to learn the language in any case;

• and, secondly, as aptly noted by Ilya Frank, ‘Language is akin to an icy hill — you have got to move fast if you want to get to the top of it,’ that is, in other words, if you don’t dedicate enough time to language learning, and keep to a fairly tight schedule, you will not be able to reach a new equilibrium point, and your acquired knowledge will slowly but surely fade away.

If you have any questions, feel free to leave them in the comments. As a reminder, Flywheel’s source code is available on GitHub and is updated and corrected whenever possible. If this rather simple but, in my opinion, very effective method of learning Spanish grabbed your attention, please create repository forks, make corrections both to code (project is written in Python and contains only about four hundred lines) and to the list of translated phrases. If you could leave a star on GitHub, that would be great.

You know what I like most about this method? After a few days of using the app, my Spanish obviously didn’t improve much. However! I gained a distinct feeling of control over the process of learning a foreign language! Previously, when using Duolingo, I had this feeling of passivity, like a passenger in a bumper car welded to the base of an amusement park ride: the car would move, then suddenly jerk to the right, then make a gentle left turn... Perhaps the trajectory was fairly good, and scientifically sound, but my issue was that it didn’t consider my previous knowledge and individual preferences. Now that both data and methods of their processing are in my hands, I feel that my little car is more or less obeying the steering wheel and is going in the direction I need.